Chapter 5

Brilliant Are the Flowers: Empire, Civilization, and Sovereignty in Chosŏn-Ming Envoy Poetry, 1457--1592

Whether as a prince jockeying for power or as the ruler of Chosŏn, King Sejo exploited his relations with the Ming to achieve his own political goals. Utilitarian in in his use of power, Sejo repeatedly disregarded the sanctity of Ming authority as he augmented his own.1 Sejo also challenged imperial ritual prerogatives by performing heaven-worship rites that were, in theory, reserved only to the Ming emperor as the Son of Heaven.2 How should these actions be reconciled with his expressions of allegiance and his otherwise dutiful observance of the obligations of a "vassal king?" Were they mere instruments for dealing with the Ming? Sejo might have thought so, perceiving his ritual performances and rhetorical declarations as necessary expedients.

Without access to the workings of Sejo's mind, ascertaining whether these performances were conceived cynically or sincerely is impossible. As this dissertation has argued, the search for sincere sentiment distracts from recognizing the illocutionary force of these performances---that is to say, the cultural and political work they were to do. On many levels, authentic emotion is irrelevant to these questions. First, the performative quality of ritual instantiates its larger normative claims; the performer may be transformed by the act, even as he appropriates its symbols.3 Viewed in the long term, repeatedly acting out the gestures of obeisance normalizes and thus legitimizes the ideas they represent. Even if Sejo remained impervious to ritual's transformative power, the bulk of the Chosŏn elite were born into a world where such rituals were already legitimate. Second, even cynical performances (so long as they are convincing) can take on a life of their own, for those who encounter them have no reason to doubt the motivations behind them.4 Ming observers and Chosŏn performers (and vice-versa) had to interact with each other on the field of this ritual, and entered into a relationship, an Eliasian figuration, where both parties played to each other's expectations. Their diplomatic declarations, once uttered, and their rituals once performed, existed on a separate communicative plane, taking on a life of their own. Specific discourses and practices then became objects of symbolic contestation, often in ways that exceeded the confines of their original purpose.

The Brilliant Flowers anthologies (Hwanghwajip 皇華集) and their surrounding practices are an example of how a Korean performance of deference to the Ming engendered a space for symbolic contestation, whose significances resonated well beyond the limits of its original, intended purpose. In this chapter, I treat the Brilliant Flowers as a novel technology of Korean self-representation that fostered a space of social interaction between Ming emissaries and Chosŏn literati officials. It also shifted the burden of empire-making to literary sociability, which enabled the negotiation of imperial ideology and its symbolism within the social space of diplomatic encounters. As a result, Chosŏn and its officials could co-opt and the co-construct Ming empire to suit their own interests and purposes.5 At stake in the practice of envoy poetry was how imperial authority was to be imagined in relation to Korea's civilizing process, an issue which spoke directly to competing claims of political sovereignty and Korea's connection to the classical past.

The Chosŏn court first published the Anthology of the Brilliant Flowers in 1457. The anthology collected the poetry exchanges between Korean officials and the Ming envoys Chen Jian 陳鑑 (1415--1471) and Gao Run 高潤 (fl. 1457), who arrived that year to announce the restoration of the Yingzong emperor to the Ming throne. Documentary evidence for how the first edition of Brilliant Flowers came into being is scant, so reconstructing its origins is difficult. There are several plausible explanations. The Chosŏn court could have printed the anthology as a favor for Chen and Gao. Or perhaps it was meant to showcase Korean literary accomplishment.6 Other scholars have suggested that the anthology reaffirmed Chosŏn fealty to an embattled Ming dynastic house. In this view, the Yingzong emperor, who had lived under house arrest after being returned to the Ming by his Mongol captors, had only been restored to power after the sudden death of his brother, the Jingtai emperor. Sejo, whose own legitimacy was vulnerable as a usurper, published this anthology to ingratiate himself with the Ming.7 Each of these explanations has its merits, but the long-term significance for Chosŏn-Ming relations lies less in the conditions of the anthology's inception than in the life it had thereafter. Whether a momentary accommodation to the whims of two Ming envoys or a way to satisfy Ming desires for recognition at a time of dynastic vulnerability, it grew over time into something much more.

After its initial printing, the Brilliant Flowers became the center of a new diplomatic tradition. Its compilation, publication, and distribution continued to the end of the Ming period. From 1457 on, the Chosŏn court compiled thirty different anthologies, one for nearly every Ming literati-led envoy mission to Korea until 1633.8 Documenting Chosŏn-Ming diplomacy of nearly two centuries, these compilations comprise around 6500 individual pieces of poetry and prose exchanged between Ming emissaries and their Chosŏn hosts.9 As a gradual accumulation of anthologies, they took form as a unified corpus only gradually. The first attempt to join these anthologies into one, comprehensive set came in 1773, when King Yŏngjo commissioned their recompilation as a part of broader court project of commemorating the Ming. With this reprinting, the anthology took on new significance as a retrospective distillation of Chosŏn's relations with the Ming court.10

The Brilliant Flowers also wove a social fabric of the personal connections it fostered and a web of intertextual links through other compilations and texts in both China and Korea. Ming envoys often kept travelogues of their sojourn to Chosŏn and included their poetry exchanges with Korean officials and poets. Ming diplomatic compositions also found their way into the personal anthologies of individual writers.11 Chosŏn participants too left accounts of these exchanges, scattered among personal literary anthologies and miscellanies.12 As a prominent gift for Ming envoys and other Ming officials, the anthology embodied the cultural and social strategies the Chosŏn court pursued in diplomacy. Its novelty, both as a technology of representation and as a product of diplomatic interaction, made the anthology's emergence a watershed moment in Chosŏn-Ming relations.

Some scholars have taken the rise of envoy poetry in Chosŏn-Ming diplomacy to signal the advent of "ideal" tributary relations and thus mark the period of the Brilliant Flowers as emblematic of Chosŏn-Ming relations in general. The turn to "literary diplomacy" (詞賦外交) indeed occurred in lock-step with political and cultural shifts at the Ming court.13 When the Ming court no longer sent special eunuch emissaries to Chosŏn to procure luxury goods and human tribute, as it had done in the early fifteenth century, diplomacy with Korea left the hands of the inner palace and entered the hands of the literati-controlled Grand Secretariat.14 The meanings of these political shifts for Chosŏn-Ming relations are several. Not least of all, with diplomacy the purview of Ming literati, the values of literary and civil culture, represented by the Brilliant Flowers, became dominant. This shift marginalized, both in practice and in historical representation, actors who were central to the exercise of diplomacy but who could not participate as social equals in literary exchange. Eunuchs, professional interpreters, and military officers were sidelined in favor of an imperial vision that centered on Confucian men of letters.15

Against this broader pattern of shifts, one must resist viewing this period of "literary diplomacy" as a distillation of "ideal" tributary relations or Chosŏn-Ming relations. For one, the gentlemanly exchange of letters documented by the Brilliant Flowers was no more an essential feature of Chosŏn-Ming diplomacy than the extortive practices of Ming eunuchs (and literati) envoys were an aberration.16 A more critical problem is that essentializing Chosŏn-Ming relations as "literary diplomacy" risks naturalizing and obscuring the historical processes that led to these shifts in the first place. If one uses the larger structural shifts to explain Chosŏn diplomatic practices, then the latter appear only as reflections of broader changes, precluding the possibility that Chosŏn practices might actually have effected structural change in the first place. This chapter contends, instead, that literati ascendancy in Ming politics alone cannot explain the domination of literary values and practices in Chosŏn-Ming diplomacy. The role of Chosŏn investment in the Brilliant Flowers must also be appreciated. This investment reinforced the political ascendancy of Ming literati in and thus encouraged the Ming to deal with Chosŏn in this channel. In other words, Chosŏn diplomatic practice and broader Ming institutional shifts not only reinforced one another, but their consonance was also a deliberate outcome of Chosŏn strategy. This entire process is missed if the emergence of this new mode of diplomacy is taken for granted.

The envoy poetry of the Brilliant Flowers, like other literary genres and ritualized practices discussed thus far, did not reflect a political order, but constituted it. The anthology's many panegyrics to empire in fact fashioned ideals of empire to envision a proper place for Korea. Through poetry writing, Ming and Chosŏn envoys co-constructed an empire whose authority was not invested in the force of arms or the movement of goods, but in a continual process of literary reenactment. The envoy poem brought the empire to life through its encomia, willing it into existence through literary fiat. The literary turn of diplomacy elevated the generative power of the imperial project as a civilizing process, which rendered Chosŏn into an object of its civilizing force. As it became a consistent part of Chosŏn-Ming diplomacy, the anthology and its literary practices reified Chosŏn's identity as a loyal tributary, but also reinscribed imperial claims into a version of empire that the Chosŏn court and its officials had desired.

The anthology's poems emphasized Korea's own independent transmission of dynastic legitimacy, the literary prowess of its people, and its claim to a common civilizational past. At the center of this was a claim to local sovereignty articulated in Korea's own autonomous civilizing process. Not all of these claims, whether by Ming envoys or Chosŏn writers, were necessarily compatible with one another. What made literary practice different from other contexts of construction, then, was the coexistence of divergent views within one body of text. Co-construction did not imply that either Ming or Chosŏn envoys necessarily shared a monolithic preconception of what the empire was. Poetic craft, then, provided the mechanisms where divergent and often dissonant views could be harmonized and calibrated, even if only within the space of a couplet or quatrain.

Finding the Brilliant Flowers: Poetic Practice in Early Chosŏn Korea

Envoy poetry was important to East Asian diplomacy before the advent of the Brilliant Flowers.17 Imperial envoys and Korean officials had exchanged poems before, a practice dating to at least the Jin period.18 Most notably, in 1396 the Chosŏn envoy Kwŏn Kŭn wrote poems with the Ming emperor Taizu, an event widely celebrated by both the Chosŏn court and Ming envoys alike through the 16th century.19

Despite numerous antecedents the Chosŏn court, by compiling and publishing envoy poetry itself, fundamentally reinvented envoy poetry. Never before had the Korean court published the envoy writing of imperial envoys. The court's publication of the Brilliant Flowers formalized poetry exchange as official diplomatic practice. The anthologies also differed in both form and content from other envoy anthologies. When Ming envoys published their own anthologies,20 they rarely included a substantial number of Korean poems, and chose instead to showcase their own writing.21 The Brilliant Flowers, on the other hand, included both Ming and Chosŏn poetry in relatively equal proportion. It highlighted the literary accomplishments of Chosŏn courtiers alongside those of Ming envoys, upholding them as cultural and social equals. By constructing these relations of parity, the anthology hoped to foster mutual identification between Ming and Chosŏn diplomats, rather than cast them only as representatives of their respective rulers. Despite the ubiquitous references to the Chosŏn ruler and the Ming emperor, the monarchs were conspicuously absent as actors, sidelined in favor of the envoys and his hosts. In sum, the anthology repositioned the diplomatic center of gravity, shifting it from a relationship between a universal ruler and his monarch to one between literary peers.

The Brilliant Flowers' encouragement of mutual identification between men of letters implicitly upheld literary values in the space of the political and the imperial. This strategic move is analogous to other practices described in this dissertation, but the Brilliant Flowers did so in a particularly self-referential way. Its title, "Hwanghwa" (Ch: Huanghua 皇華) suggests an inextricable link between literary practice and imperial power. The polysemy of the two characters, hwang (Ch: Huang, imperial/brilliant/august) and hwa (Ch: Hua, efflorescence/civilization/China), allows the title to be read as "august efflorescence (civilization)," or "imperial China." This latter, literal reading of the term hwanghwa, however, was never explicitly employed in the Brilliant Flowers itself. When both Chosŏn and Ming envoy writers referred to the title of the anthology, they pointed to the term's locus classicus, a piece in the Classic of Poetry. The poem, "Brilliant are the flowers" (Ch: Huanghuang zhehua 皇皇者華), was so titled because of its affective image of flowers blooming brilliantly across the landscape as a dutiful Zhou royal emissary traveled to feudal states to procure virtuous men for his ruler.22 By couching it in the world of the classics, envoy poetry transformed the Chosŏn and the Ming into inheritors of a hallowed tradition, fostering correspondences that transcended distinctions of time and space. In this rendition the Ming envoy is the representative of the Zhou king who travels to the feudal state of yore, now imagined to be Chosŏn, where virtuous men and beautiful customs await his discovery.

The connection to the classical world of the Zhou depended on an appeal to a common literary tradition through the writing of poetry itself. Cultural identification implied by writing the same poetry helped construct a broader cultural imaginary. Through a shared knowledge of classical texts, whether the received traditions of the Zhou Dynasty, the writings of Song Neo-Confucians, or the poems of Tang masters, the literati of both China and Korea were by the fifteenth century writing within a larger "imagined community" (only to borrow the language of Benedict Anderson) with a common script.23 A shared cultural imaginary seemed to enable the expression of political allegiance. In what he calls the "complicity between Chinese classical literature and the imperial system," Stephen Owen has argued that poetic composition confirmed an individual's loyalties, not to the state and emperor per se, but to the ideological world-view that upheld the imperial system. The poem need not declare 'I am loyal,' for it demonstrated a thorough assimilation of the correlative cosmology on which the government's authority, even its justification to exist, is founded."24

These observations of the use of poetry imperial in the civil service exams appear to apply to envoy poetry, but only on the surface level. The Korean envoy poem both assimilated the correlative authority of imperial authority and declared loyalty to it. Moreover, the Chosŏn court's encouragement of envoy poetry also suggests its allegiance to the imperial view of the world. Modern scholars have therefore understood the Brilliant Flowers as an affirmation of a shared value system embodied in the literary tradition. Du Huiyue, for instance, takes envoy poetry as clear evidence of both the Chosŏn court's unquestioned loyalty to the Ming and the admiration of Chinese culture by the Ming elite.25 Such arguments seem compelling because classical poetics ascribes poetry, especially the si-poem (Ch: shi 詩), the power to speak to the immediacy of human emotions, and thus read them as authentic representation of an author's sentiments (i.e. shi yan zhi 詩言志). As such, they are also seen to be the genre most reflective of the author's interiority, and by extension, his moral character.26 When the si-poem is assumed to have lyrical authenticity, the envoy poem thus becomes a reliable indicator of the subjectivity of Chosŏn and Ming writers. What better demonstration of Chosŏn's "admiration of China" (mohwa chuŭi/muhwa zhuyi 慕華主義) and commitment to "Serving the Great" than the poems that expressed these sentiments?

There are several problems with these views, all tied to the hermeneutics of reading si-poetry. Proceeding from classical models to interpret poetry by assuming its lyrical authenticity risks neglecting the social and political contexts of their composition. Moreover, in the Chosŏn context, it ignores a history of centuries of appropriation and reinvention. Korean rulers had long appropriated the technologies and ideologies of empire and intertwined their own legitimacy with the symbolic authority of emperors. For Chosŏn envoy writers, the "correlative cosmology" tied the poem not only to imperial authority, but the Chosŏn kingship as well. Seeing poetic practice only as a reflection of politics also implies a recursive and reductive determinism. Certainly, literary practice can and does reflect diplomatic norms, for political hierarchies, ideological underpinnings, and institutional arrangements all become visible in the rhetoric and practice of the envoy poem. But, if poetry is understood in terms of its ability to reflect the "real" (constituted by things such as power, prestige, hierarchy, or structure, which often are in fact scholarly abstractions), it suggests one-dimensional, unidirectional relationship between politics and literary practice, with the former determining the latter. It discounts the possibility that the literary production could also shape the political. As a form of representation, literary exchange was part of a political theater, performed with instrumental aims.

Classical formulations notwithstanding, later writers of poetry saw the performance and artifice inherent in literary craft as undercutting the sentimental spontaneity and authenticity of the poem, and thus its moral value as a whole.27 Early Chosŏn courtier-poets shared these anxieties over craft and its threat to poetry's moral value. The belles-lettres (sajang/cizhang 詞章), which included poetry, had a particularly uneasy relationship with both Neo-Confucian learning and the demands of statecraft. Detractors pointed to its "frivolity,"and found it "insignifican [t ]" to a literati's proper pursuits, namely moral cultivation and classical scholarship.28 Although the belles-lettres eventually occupied a central place in Korea's civil service exam curriculum, their status as a legitimate scholarly pursuit was tenuous during the Chosŏn's earlier years. The Chosŏn founder had in fact abolished the poetry examination and his successors did not restore it until 1453.29

Restoration of the poetry examination was due to the the growing importance of literary exchange in diplomacy with Ming envoys. As Peter Lee has stated, "if the government failed to nurture talented writers, the country would fare poorly in international relations."30 One Chosŏn official, Yi Ch'angsin 李昌臣 (1449--1506), cautioned his king against neglecting belles-lettres, in spite of its "irrelevance to governing the country," precisely for this reason.31 The arguably utilitarian defense of the state patronage of poetry may appear to diminish its intellectual and cultural importance, such a discourse belied both the political and ideological role it played at the Chosŏn court. Poetry writing in diplomacy, however, was not simply a matter of entertaining Ming envoys, for Chosŏn court poets invested their writing with moral and political claims that impacted the legitimacy and authority of the Chosŏn state on the one hand, and the ideological construction of the Ming and its empire on the other.

The envoy poet was ever aware of the public nature of his writings, visible not only to his counterparts on the outset, but with their systematic publication by the Chosŏn court, privy to posterity. This awareness did not preclude assertions of authentic sentiment, but this emphasis points to the problems of trust and sincerity inherent to diplomacy.32 The purported lyrical authenticity of the poem then went hand in hand with the need to establish trust with one's audience by assuring them of one's sincerity. Like in other diplomatic genres, such as the p'yomun memorial discussed in Chapter 1, sincerity was a construct of the genre. These practices reflected ideology and structure, but only because its ideology and structure emerged from them.

The intertwined political use and social practice of poetry should reveal where the classical formulation of lyrical authenticity is inadequate. Envoy poets wrote for social moments. The anthology's paratexts: prefaces, titles, and postscripts, indicate with specificity their social function.33 Chosŏn and Ming envoys often wrote poems to each via a popular form of linked composition, called "rhyme-matching" (ch'aun/ciyun 次韻).34 Rhyme-matching required responses to a predecessor's poetry to use the same rhyme words, a practice conducive to the recycling of tropes and images. Since Ming envoys often responded to predecessors separated by decades, if not centuries, this practice granted diplomatic relations between the two states a semblance of timelessness. The Chosŏn court reinforced this image by carving these poems on plaques and steles that adorned the sites Ming envoys visited. Both these envoys and their Chosŏn hosts consulted prior editions of the Brilliant Flowers as models for their own compositions. As it came to be used and reused through the 17th century, the Brilliant Flowers emerged as a repertoire of knowledge for both Chosŏn and Ming envoys.35 All in all, the poems of this anthology, ranging from brief quatrains to extended meditations sustained over sixty or seventy couplets, were not self-contained pieces of private introspection, but products of literary sociability.36

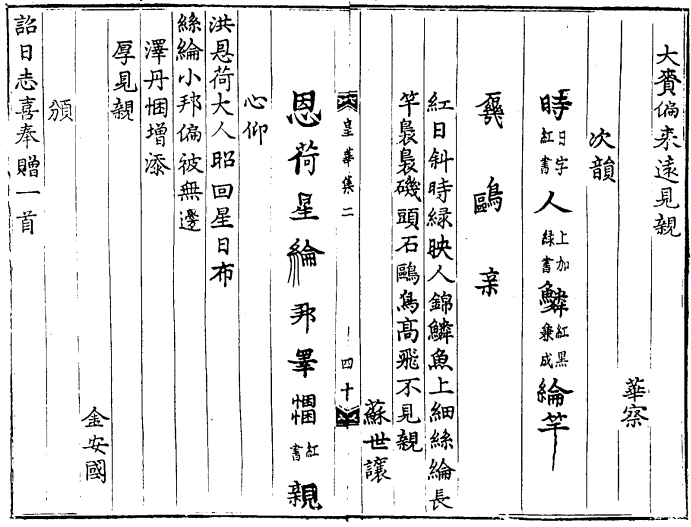

Figure 3: A Tongp'ach'e poem

A considerable number of pieces were meant to demonstrate literary virtuosity. The hwemunche poem (Ch: huiwenti 迴文體) and the tongp’ache poem, shown here, (Ch: dongpoti 東坡題), for example, are featured extensively in these anthologies. Hwemunche, lit. “Reverse-text poems,” were semordnilaps, compositions that showed perfect poetic prosody whether read forwards or backwards. Tongp’ache poems involved writing a poem with characters using modified strokes, where color, length, orientation and composition sometimes insinuated whole phrases. For example, the character for “mountain,” san/shan 山 written in green ink would be read as “green hills,” (ch’ŏngsan/qingshan 青山). Example from the 1539 HHJ, reprint from the SKCM pt.4, v.301

Literary exchange, as a medium of sociability, often enshrined a sense of personal friendship between Ming literati envoys and their Chosŏn counterparts. In their exchanges, they often expressed sentiments they hoped would transcend both political geography and human time.37 The social embeddeness of envoy poetry is also corroborated by the intertextual relations an individual poem has with other compositions and with other genres of writing. Chosŏn miscellanies, like the P'irwŏn chapki of Sŏ Kŏjŏng or the P'aegwan chapki of the interpreter Ŏ Sukkwŏn (魚叔權 fl. 15th century), which documented this sociability, also reveal a prevailing concern with literary reputation and competition.38 Literary virtuosity was valued for both Ming envoys and Chosŏn officials, as anecdotes about their exchanges were abound in these selections. In the judgment of these Chosŏn writers, a Ming envoy's character was reflected in a combination of both his literary ability and his moral behavior, with few receiving unqualified praise in both. By the same token, a Chosŏn poet's abilities reflected directly on the overall literary attainment of Korea itself.39

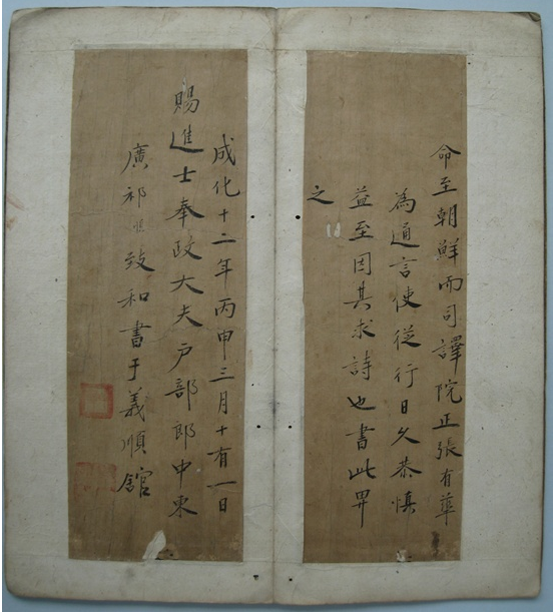

Figure 4: Poem by the 1476 Ming envoy Qi Shun

Both expressions of friendship in poetry and acts of literary competition proffered a sense of social parity rooted in a common script and literary tradition.40 When a Ming official could see a Chosŏn counterpart not simply as a representative of a foreign (or worse, barbarian) ruler but as men of letters, then their mutual identification could also suggest the possibility of cultural parity between the Chosŏn and the Ming. The Chosŏn court thus tried to foster this identification, selecting only the best literary talents to be members of the envoy reception committee.41 Hoping to further showcase Korean talent, it published the Brilliant Flowers to secure imperial attention for Chosŏn writers, and by extension, Korea's cultural accomplishments. In this manner, sociability and literary talent went hand in hand. Even as the Brilliant Flowers clearly coded the hierarchical distinction between the Ming emperor and the Chosŏn ruler,42 it posited an alternative relationship of parity, in which the Chosŏn and the Ming were peers in cultural attainment.

The Chosŏn court and its scholars made considerable efforts to claim this parity, but struggled against Ming condescension.43 The mid-Chosŏn miscellany writer, Yu Mong'in 柳夢寅 (1559--1623), who traveled several times to the Ming as an envoy, once complained that "over these hundreds of years ....not a single piece of writing from our country [i.e. Korea ]" adorned the edifices along the "several thousand leagues" of road to Beijing. Yu was miffed that Chinese literati have "looked down upon [Koreans ] since antiquity" and did not treat them as social or intellectual equals.44 This frustration may have been related to Yu's oft-cited dismissal of the Brilliant Flowers, a collection, that was in his words, "not [worth ] transmitting to posterity," and doomed to "obscurity." To him, the court squandered the opportunity because it had "indiscriminately" selected court poets to receive Ming envoys. Chosŏn poets thus failed to shine when the kingdom's prestige was at stake and the Brilliant Flowers did no more than "elicit the derision of men from both man and heaven" (貽笑天人).45

Yu Mong'in's criticisms anticipated what the late Ming-early Qing literary critic (and self-identified Ming loyalist) Qian Qianyi 錢謙益 (1582--1664) wrote when he read the Brilliant Flowers. He too found its poems lackluster, "bereft of remarkably beautiful verses." Qian explained it to be a result of the "plain and flat" literary style of Korean poetry. Ming envoys, on the other hand, had to "weaken their [own ] verses to accommodate them," in keeping with the principles of "cherishing men from afar."46 In other words, Qian excused the mediocre Ming writing by claiming their authors wrote plainly on purpose in order not to embarrass their hosts by showing off their talents: a sacrifice of personal literary repute for the larger goals of maintaining cordial relations and demonstrating imperial magnanimity.47 Yu Mong'in would have undoubtedly disagreed with Qian. Responsibility for the poetry's poor quality fell on both Ming envoys and the anthology's compilers. According to Yu, the Chosŏn court hoped to curry favor with Ming envoys and dared not refuse even a single poem that the Ming envoys presented. Without discriminating between the "beautiful and the ugly," they included everything.48 Yu and Qian blamed the anthology's diluted quality on different parties, but their diagnosis was essentially identical. Accommodation of sociability and political exigency, whether by the Chosŏn compilers or the Ming poets, was ultimately at fault.

Both Qian and Yu's critiques might have suggested that collection ultimately failed to secure Korean literary reputation, but these later judgments must be accepted only cautiously. Dismissals of literary quality only underscored the political, social, and ideological function of this anthology. A reader in search of timeless poetry may be disappointed by the Brilliant Flowers' heavy-handed ideology and ornate imagery, interspersed with the doggerel of sociability. Those in search of its political symbolism, however, will find much to appreciate.49 Qian Qianyi may have dismissed the anthology's literary merits, but appreciated it for the reverence it showed the Ming.50 In Chosŏn, the Brilliant Flowers was reprinted shortly after the Imjin War in celebration of Ming military aid, but was largely ignored after the Ming's fall. When King Yŏngjo ordered its recompilation, it took years to collect the scattered volumes to complete a reprinting. For King Yŏngjo too, the Brilliant Flowers represented less Chosŏn's literary attainments than evidence of Chosŏn Korea's unwavering, if nostalgic, loyalty to the Ming imperium.

The Brilliant Flowers were appreciated first and foremost as an encomium to empire. Their superimposition of the literary, social, and political in one space, a result of poetry written to satisfy the needs of a moment, made them vulnerable to later critical appraisals, but it is precisely the feature that makes these anthologies a useful window into the culture of diplomacy of this period.51 The superimposition generates several points of tension, namely the function of the literary to overwrite political and social friction and the multivocality of a literary sociability at the service of political ideology. The task of literary encomium precluded overt discussion of contentious areas in Chosŏn-Ming relations. A veneer of high imperial rhetoric celebrated the beautiful and the virtuous, glazing over possible sources of animosity and conflict, to construct a harmonious social space paralleling the tranquil relations between the two courts.

Multivocality was integral for the Brilliant Flowers' effect of encomium. The Ming could always count on its own officials to sing its praises, but here, the celebration of empire ceased to be a solipsist's exercise in self-adulation. Chosŏn officials, by literally resonating with Ming ambassadors, confirmed the authenticity and legitimacy of Ming imperial claims. As disparate parties came together and rhymed in their celebration of the Ming, they co-produced the empire in discourse. Yet, this multivocality cut both ways. Even as these envoys wrote to harmonize in ideology, rhetoric, and literary style, fractures and divisions still come to the fore as the diverse participants of the Brilliant Flowers advanced competing narratives of what empire was and should be.

Imperial Encomium and the Academic Style

The poetry of political encomium in Ming literary history is associated with the so-called "Secretariat Style" (Ch: taige ti 台閣體), so-called because it evolved from the poetry of the Three Yang's 三楊, Yang Shiqi 楊士奇 (1364--1444), Yang Rong 楊榮 (1371--1440), and Yang Fu 楊溥 (1372--1446), three figures who made their literary careers in the Ming Grand Secretariat.52 Though these men only held low-ranking posts as academicians53 of the Hanlin Academy54, they occupied a keystone position as liaisons between the emperor and the civil bureaucracy.55 By virtue of both the prestige and concrete political power concentrated in such figures, these academicians exerted enormous influence on both literary trends and political decision making. Their "Secretariat Style," said to "adorn Great Peace" (Ch: fufu taiping 黼黻太平) and "sing the accomplishments and virtues" (Ch: gegong songde 歌功頌德) dominated the Ming literary scene through the end of the reign of Emperor Yingzong in 1464.56

Conventional explanations of the decline of the "Secretariat Style" points to its gradual divorce from social reality. Attributing its dominance to the Ming's tangible prosperity during the Yongle and Xuande reigns, debacles such as the Battle of Tumu turned the "Secretariat Style" into an artifact of courtly conceit.57 It was ironically the wane of Ming power that brought this academic poetry to Chosŏn. In fact, the first envoy to engage in extensive poetic exchange with Chosŏn officials, Ni Qian 倪謙 (1415--1479), who arrived in Chosŏn to proclaim the accession of the Jingtai emperor, has been described as a representative Secretariat poet.58 Ni Qian was not alone among the mid-Ming envoy-poets associated with this court-centered literary circle. The 1457 envoy Chen Jian and the 1460 envoy Zhang Ning too were also well-known academic poets of this period.59

Ni Qian came to Korea in a time of unusual political uncertainty, but in fact many of the Brilliant Flowers were compiled during moments of transition. Since Ming literati usually only led embassies to announce the accession of a new emperor or the investiture of a Ming heir apparent, on many occasions the "Sagely Ruler" on the throne was but newly crowned, untested in rule. Chosŏn's affirmation of loyalty to the Ming was doubly significant in such times, as it insisted a stereotyped image of the imperial person that was consistently sagely, benevolent, and perfect in these literary encomiums. Just as, in the words of Gari Ledyard, "each new diplomatic pouch to Korea" brought a message that insisted on the perfectibility of imperial virtue, in spite of the "tyranny and delinquency" of the Ming emperor, the envoy poems of the Brilliant Flowers proscribed an imperial personality equally disembodied from tangible reality.60

The primary audience for the Brilliant Flowers were not Ming emperors, but the Ming Secretaries and Hanlin Academicians charged with actualizing a vision of civil rule and who often had to negotiate and contend with the highly personal and arbitrary style of Ming sovereigns. By describing emperors in this manner together, Chosŏn and Ming literati constructed a shared ideal of empire that could also be a vehicle for censure.61 Disembodied ideals of empire were constructed against the imperfect reality of imperial virtue that Ming officials and Chosŏn courtiers alike knew too well.62 Detachment did not make the rhetoric and imagery of encomium meaningless; instead, it should be read as an elucidation of an institutionalized ideal, an illocutionary act that reinforced not just the terms of Chosŏn-Ming relations, but also the standards and values of empire. These poems fabricated an empire in the abstract, not a human emperor.63

The features of the "Secretariat Style" also define the poetry of the Brilliant Flowers. As imperial academicians, secretariat poems wrote on imperial command. Court life: banquets, royal outings, ascent poems, painting inscriptions, compositions on history, and seeing off fellow officials were among its major topoi.64 The 1460 envoy Zhang Ning's "Ascending the tower at the Hall of Great Peace in sixty rhymes" is a quintessential example of the kinds of scenic writing common to both the "Secretariat Style" and the Brilliant Flowers. Aptly named, for it describes a vision of grand peace that appeared during the ascension of a tower by the same name. Located in the residence for Ming envoys in the Chosŏn capital, the Hall of Great Peace (T'aep'yŏnggwan 太平館) was the site for banquets held in an envoy's honor. Zhang's postface to his poem written on this occasion tied literary enterprise with the political aspirations of empire. Conventions of ascending high, scenic description, and historical rumination fuse together in this piece:

In the spring of the fourth year of the Tianshun reign, I came as an envoy to Chosŏn on imperial orders. I ascended high and looked off into the distance, thinking of the imperial capital and looked around me at the kingdom [of Korea ]. The timing of nature, the affairs of men, the scenery and objects, mountains and rivers-- the diversity of things hidden and apparent---they all come into my mind and gaze.65

The envoy-poet mediates between the generative energy of nature and the productive power of writing. Together they become interchangeable with imperial universalism. The natural scenery of Chosŏn, and affirmations of its loyalty to the Ming, became celebrations of the splendor universal rule and its cosmic import. Lines like, "The grace of heaven and earth is enjoyed by all the same; / Among the civilized and the barbarian, none do not pay obeisance to the origin,"66 compared the bearing of tribute by foreign parties to the all-embracing reach of heaven and earth. Because the Ming had "inherited the statutes of the Zhou," (膺周典則) its "territory covered all that was once the Han's domain" (輿圖盡屬漢提封).67

Favorable comparisons to past dynasties and ancient Sage Kings in the lines of the Brilliant Flowers were not in themselves interesting because they were common in other imperial paeans, but they were deployed in conjunction with favored tropes particular to the Brilliant Flowers. Imperial universalism was one of them. Chosŏn writers who responded to Ming envoys in verse made use of similar devices. The restoration of Ming Yingzong to power in 1457 elicited the lines: " [the emperor ] again pacifies the Jade Domain [i.e. the empire ]; proclaiming [his rule ] within and without, he begins anew with all-under-heaven, seeing it all with one heart." Though it opens with an oblique reference to Yingzong's restoration, the tract immediately turns away from the imperial person towards the quality of the Ming's impartial gaze.68 Chosŏn diplomats often appealed to this impartiality, when they made demands upon Ming emperors and officials alike. Tied to notions of universal empire, this trope carried a dual function.69 It praised the imperial project while committing it to a particular way of treating Korea, an "insignificant fief that occupied the sea's margin." The Ming, by "proclaiming the proper lunation to the eight frontiers" had demonstrated its commitment to "see Korea just as its own interior territory."70

The deployment and elaboration of this particular trope distinguishes the poetry of the Brilliant Flowers qualitatively from the usual academic encomium. While Ming encomiums certainly possessed descriptions of all-encompassing majesty, the envoy poem had to make such visions concrete and applicable to Korea. Rather than an aloof imaginary of all-encompassing inclusivity radiating from an imperial center, the gaze of this imperial vision fell concretely on a particular space. These envoy-poets had to integrate Chosŏn within an imperial vision in the presence of Chosŏn observers. With the Korean audience contributing its own articulations of that vision in its matching verses, the impartial imperial gaze, then, was neither the private conceit of Ming officials nor a fantasy of their Korean hosts. Statements such as "In a Sagely Age of August Peace the airs are harmonious; / Heaven's grace goes far to the East of the Sea [i.e. Korea ]" (聖世隆平和氣洽 天恩遙到海東頭)71 may appear as unequivocal expressions of Ming magnanimity, but lines like the following in Zhang Ning's "Hall of Grand Peace" also pervaded these exchanges:

In the Eastern Land the culture of letters has always been good, Since long ago, the Central Court had bequeathed upon it wonders. A vassal screen for the imperial house, it observes the decorum of virtue; Its ceremonies model Sagely Forms, consoling the downtrodden people.72

Korea's integration into this vision of empire, projected from a vista overlooking the Chosŏn capital, depended on the mutually constitutive effects of resonance and reciprocity. The empire produced through this act of viewing and writing propounded a universalism that could make irrelevant the questions of geographical distance and cultural difference: "The road reaches the ends of the water and land, and the sounds of the country are different; / [but ], spring fills qian and kun [i.e. Heaven and Earth ], and the scenery is all the same." In the next two dozen or so couplets, Zhang described Korea's scenery as one of spectacular beauty, owing to the resonance between nature's cosmic magnanimity and the political harmony brought by Ming rule: "The passing years have now changed again with harmonious light/ Even small things are embraced by Creation's force" (流年又遂陽和換 微物均為造化容). The splendors of nature generate profusely from his brush, quickening with the coming of spring.73

The generative power of spring functioned as a metaphor for the power of literary production. In turn, writing was a vehicle of the empire's civilizing influence. The literary incorporation of Chosŏn's landscape into an imperial gaze was inseparable from political implications. Like in the poem of the 1537 envoy Gong Yongqing 龔用卿 (1500--1563), "Crossing the Yalu" (渡鴨綠) where the imperial messenger's passage across the Yalu River awakened the flowers on the river's banks, the envoy, an agent of empire, literally brought civilization to distant lands. For Gong, all this was self-evident confirmation that "literary influence belonged to one rule.74 In the logic of this literary device, celebrations of Korea's own literary accomplishments could then always further indicate the Ming's achievements. The 1476 envoy Qi Shun's "Rhapsody on Phoenix Hill" (鳳山賦) illustrates this motif. A place in Chosŏn so named because a phoenix had once alighted upon it, Qi ruminated on the significance of the phoenix as portents of a pacific age. Dismissing past examples of descending phoenixes as "marvels of a moment," Qi exclaimed that "now with a Brilliant Sage above, the literary course flourishes, extending from the Nine Realms within to the distant marches without; the transformations of virtue have spread vigorously in harmony and exuberance."75 Along with other auspicious signs that demonstrated the Ming's splendor, the "colored bird of Korea too comes to meet a glorious dawn." Qi asks, rhetorically, "does this not show the renewal of the Eastern Fief's civilization, and demonstrate the complete triumph of our Court's transforming power?"76 Literary enterprise, Ming universalism, Chosŏn's allegiance to empire, and the social space of envoy writing reinforced one another. In this imagination of the imperial, sovereignty was expressed not in terms of territorial rule or military prowess, but in monopoly of the civilizing process.

Imperial sovereignty, however disembodied from an actual ruler, was nevertheless squarely situated within the imperial tradition. The Ming claimed to inherit the legacies of its predecessors, but also tried to show it had surpassed them. The empire was a legible political imaginary insomuch as it was connected to institutions and practices retrieved from the dynastic and classical past. Korea played a critical role in demonstrating Ming superiority. A Ming local official, Xue Yingqi 薛應旂 (1500--1575) pointed to the unprecedented arrangement the Ming had with the Chosŏn, in his preface to the now lost Korean travelogue of his friend, the 1537 vice-envoy Wu Ximeng 吳希孟:

The Chosŏn of today was once the country of Jizi [Kija ] in the Zhou. During the Han, it was the prefectures of Lelang and Xuantu. It was always a place where [civilizing ] influence (shengjiao) reached. When the mangniji (i.e. the military dictator Yŏn'gaesomun) brought tumult during the Zhenguan period [627--649 ], the dispatch of China's troops could not be avoided .... Only with the rise of the Ming did they sincerely turn towards transformation [i.e. show their allegiance ], and came [to pay tribute ] ahead of the various barbarians---A great triumph of our Emperor's diffusion of culture.77

Korea's submission to the Ming made it superior to previous imperial dynasties. The Ming earned Korea's submission, not through the force of arms, but through its literary and cultural power. This articulation of Korea's significance in the rhetorical logic of empire denied Chosŏn any agency over the civilizing process. Korea's only role was in "turning to civilization;" it could not create its own. Furthermore, the reasoning that underlay Ming superiority over its Han and Tang predecessors presumed the legitimacy of the Ming's sovereign reach, that Korea, as the location of the former Han prefectures of Lelang and Xuantu, an integral part of the empire itself.78 The Ming's achievement is only legible within a logic of imperial irredentism, where figurative assertions of imperial universalism easily slips into a literal claim of imperial dominion. In this imperial vision, why should Korea, as an independent state, exist at all?

The Problem of Civilization: Eastward Flow or Eastern Spring?

When imperial envoys arrived in Korea, they witnessed a society that appeared to them in many ways similar to their own. The Song envoy Xu Jing already noted in 1123 the flourishing of Confucian literati culture and presence of familiar political institutions.79 Korean civil service exams, an organized bureaucracy, and court ceremonial paralleled imperial practices. Ming envoys, like Dong Yue 董越 (1430--1502) of the 1488 mission, also remarked these similarities. Though he noted peculiar differences, such as the absence of precious metals as currency and the existence of a local aristocracy, the yangban, Korea was at least legible to his gaze.80 Unlike other peoples on the empire's frontier, whose customs were often dismissed as simply "barbaric," Ming envoys like Dong Yue lauded Chosŏn observance of Confucian rituals.81 Korea's use of literary Chinese and the performance of rituals while wearing "robes and caps" (衣冠) made Korea uncannily familiar to these literati, most of whom would have never had an opportunity to travel beyond the empire's interior. The ritual performances at the Confucian temple most firmly demonstrated this legibility. The 1537 envoy Gong Yongqing thus wrote of his visit to the one in P'yŏngyang, "The East holds on to the teachings of wen, / Revering the way at the temple's worship" 東方守文教 敬道崇廟貌. Literary and civil culture, rooted in Confucian teachings, was respected in Korea as well. But, for Gong, this reverence for "Confucian airs" was the result of "Imperial transformation," a tangible testament to the "effectiveness" of its "gradual flow" 皇化重儒風 漸摩知所效.82

Although it was not explicit in Gong's poem, the "flow" of civilization was always conceived as trickling from China eastward. This "eastward flow of civilization" (東漸之化) was a common idiom in the Brilliant Flowers. Drawn from the well-known passage in the "Tribute of Yu" in the Book of Documents it expressed the universalizing aspirations of empire.83 The mid-Ming author of the Supplement to the Extended Meaning of the Greater Learning (大學衍義補) Qiu Jun 丘濬 (1420--1495), who emphasized the importance of statecraft to the Neo-Confucian program of self-cultivation, explained it as thus: "the rule of an enlightened sage ... flows like water until it reaches the ocean to cover all, much as there is nothing that heaven does not encompass; all that heaven encompasses can be reached by the sage's moral transformation."84 The terms used to express this "civilization" force, shengjiao (Kr: sŏnggyo 聲教) are variably translated in scholarly literature, likely because it defies an easy equivalence, encompassed a host of related meanings.85 Qiu identified the two elements of this concept, sheng and jiao, as complementary mechanisms. While sheng pointed to "that which arises here and is heard by those afar," jiao referred to the "models established here and are emulated from afar." The process of transformation (hwa/hua 化) thus entailed not direct intercession, but influence that spread naturally through moral rectitude. Its universal reach was achieved through the admiration of others who emulated one's moral example.86 Elsewhere in his Supplement, Qiu Jun, who likely interacted with Chosŏn embassies during his tenure as a Ming grand secretary, praised Korea for "observing their station" (安分守) and "reverently submitting to the imperial court, coming to pay tribute at all times, without neglecting their ritual duties."87 He explained that the Ming's "virtuous transformation was what has moved" Chosŏn to submit and saw the Korean case as a tangible actualization of the classical ideals he expounded.88

Korean writers also actively participated in this discourse of civilization. The Brilliant Flowers offers a wealth of such Korean examples, but when Korean writers wrote of civilization's "eastward flow," they often emphasized Chosŏn's primacy. Kim Su'on 金守溫 (1409--1481) in his response to the 1476 envoy Qi Shun's "Rhapsody on Phoenix Hill," is one example. By stating that "though our state is said to be [but ] one corner [of the world ], it is first to receive the eastward flow of civilization."89 Kim turned an expression of the universal moral authority of the Son of Heaven into a demonstration of Korea's privileged position. Ming rule was to be impartial, but it was supposed to be especially impartial to Korea.90 As it is often the case in Korean use of classical allusion in diplomacy, its interpretive significance was seldom confined to the readings of Chinese commentators, and were adapted in advantageous ways to the Korean situation, often quite subtly.

The universal mode that Kim elucidates, however, was not the only possible vision of empire. The Song Neo-Confucian Zhu Xi, whose ideas were foundational to both early Ming and Chosŏn thought, insisted that there were distant reaches, the so-called huangfu (Kr: hwangpok 荒服), where civilizing influence could not reach.91 In other words there were two competing theoretical visions at work, one where influence could extend infinitely, and another in which geography placed a natural boundary to its extension. The question that remains was where Korea fit into this scheme. Was it a place where imperial influence could reach, or a place beyond its pale?

As discussed in chapter 2, the first Ming emperor Hongwu chose the latter interpretation when he rejected the Chosŏn founder's request for investiture.92 He had told the Chosŏn court to "do [the activity of ] shengjiao on one's own terms" (聲教自由). The Hongwu emperor denounced Korea for its recent political turmoil and clearly demarcated China as "where moral norms rested" (我中國綱常所在) and Korea as a "land separated by mountains and beyond the sea." Its status as a land of "eastern barbarians" was "heaven-made" so as "not to be governed by China." Hardly statements of approval, Chosŏn's independence was founded on its unchangeable and preternatural barbarity.93 A later edict to the same effect was promulgated in 1396. While Ming Taizu refused investiture on the grounds that "Chosŏn ... was the country of the Eastern barbarians, with different customs and distinct mores," and had no desire to make it his vassal, he also chastised T'aejo for being "stubborn, querulous, cunning and deceiving." His acknowledgment of Korean autonomy by relinquishing claims of cultural sovereignty over it was tantamount to stating that Korea was too "barbaric:" culturally unprepared for and morally undeserving of his imperial grace.94 Ming Taizu also stated, however that Korea "should have a king," and implied that he would "make [T'aejo ] a king," [i.e. formally invest him ] if his "character improved." In other words, if Korea can prove that it was amenable to imperial control, the Ming ruler would grant Korean rulers investiture, and make him a formal vassal, bringing Korea within the civilizing power of the imperial court.

For Ming Taizu, "permitting" Chosŏn to carry out the civilizing process (sŏnggyo/shengjiao) "on one's own terms" was a rejection of Chosŏn's cultural and political legitimacy. It provided grounds for denial of investiture. After Ming Taizu's death, however, Chosŏn rulers not only received Ming investiture, but also appropriated Taizu's original proclamation and inverted its original logic. Whereas receipt of investiture would theoretically annul Chosŏn sovereignty over the civilizing process, early Chosŏn statesmen employed Ming Taizu's phraseology to sanctify Korea's political and cultural autonomy.95 During the reign of King Sejong (r. 1418--1450), the Chosŏn court undertook numerous projects of political legitimation that demonstrated its local sovereign claims. Sejong sponsored, for instance, the invention of the Korean alphabet as a "local" vernacular script. His astronomers apportioned an "Eastern" heaven that was reserved for Chosŏn.96 In this formative period, court officials triangulated classical prescriptions and contemporary Ming practice with native customs to revamp Korean state ceremonies, royal marriage practices, and diplomatic protocols and other rituals under the auspices of local sovereignty.97 Belief in the legitimacy of Korea's own institutions and native traditions, allowed Chosŏn officials to defend them, even against the criticism and intervention of Ming officials.98

These discourses of Korean cultural sovereignty notwithstanding, Ming envoys and Korean officials still asserted that the emperor's shengjiao did in fact extend to Korea and superimposed Ming claims over the Chosŏn court's own ones. When examined on these grounds however, this idea of Ming influence was at best an abstraction. Since shengjiao did not just articulate claims of political sovereignty, but also referenced more concretely the quotidian actions of "civilizing:" reforming customs, building schools and shrines, and extolling moral virtues. In other words, the civilizing project required some level of activism, either on the part of the state or local literati.99 The "civilizing process" in Chosŏn, defined through the dictates of Confucian statecraft, ritual, and social mores, was effected through a concerted effort on the part of activist officials at the early Chosŏn court to enact social legislation.100 The power of "civilizing" (sŏnggyo/shengjiao) was also an expression of political sovereignty and thus became a way to legitimize the Chosŏn court's intervention into local customs, ritual practice and social mores.101 The tangible activities of "civilizing" were all tied to court initiative.102 Despite (or rather because of) its "imperial" associations, the Chosŏn court did not hesitate to characterize its own rule over Korea in these same terms, though it sometimes refrained from adopting the all-encompassing, cosmic universalism of imperial rhetoric.103

The Ming court had nothing to do with any of these initiatives, but that did not stop Ming observers from casually attributing them to the Ming's virtuous influence. From the vantage point of Ming court, the perspective had its merits. Ming officials, like Qiu Jun, for example, noted the Korean desire for Chinese books.104 Important imperial commissions, such as the History of the Song Dynasty (宋史) and the Great Compendia of [Neo-Confucian Commentaries on ] the Five Classics, Four Books, and Nature and Principle (五經四書性理大全) had been requested by the Chosŏn court or bequeathed via tribute envoys.105 The subsequent flourishing of Confucian culture in Chosŏn was then attributed to this transfer of knowledge, one made possible by Ming munificence. When the Yongle emperor granted a copy of the royally commissioned the Great Compendia, his edict called this gift (along with other, more worldly items), a demonstration of "extraordinary favor" and encouraged him to "read books diligently."106

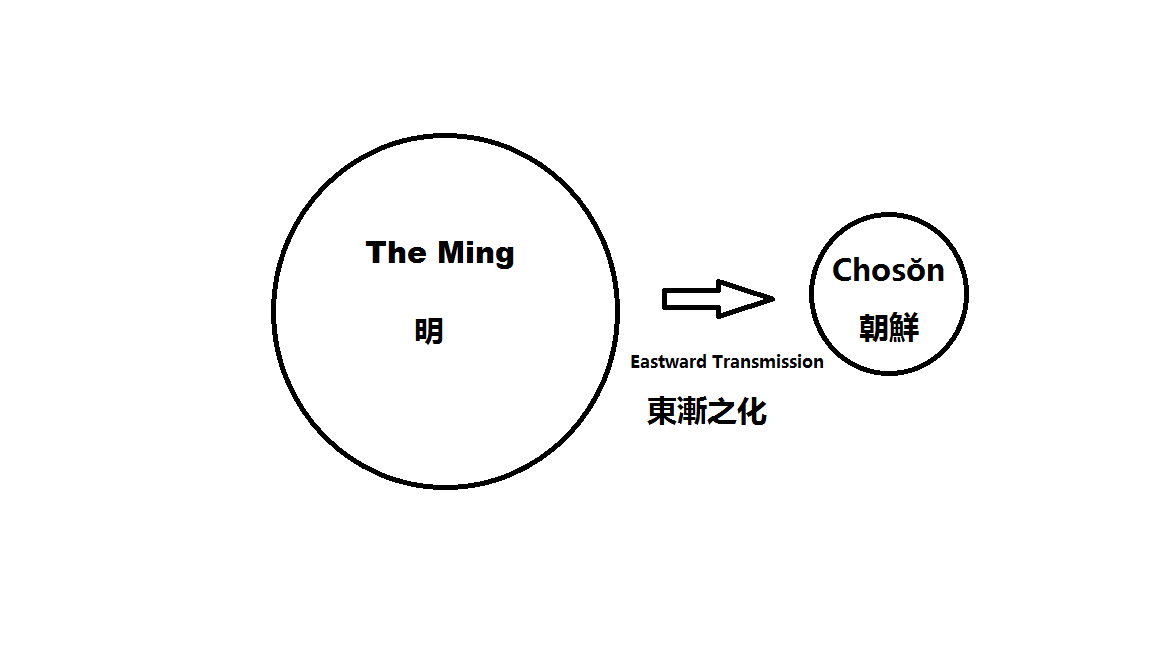

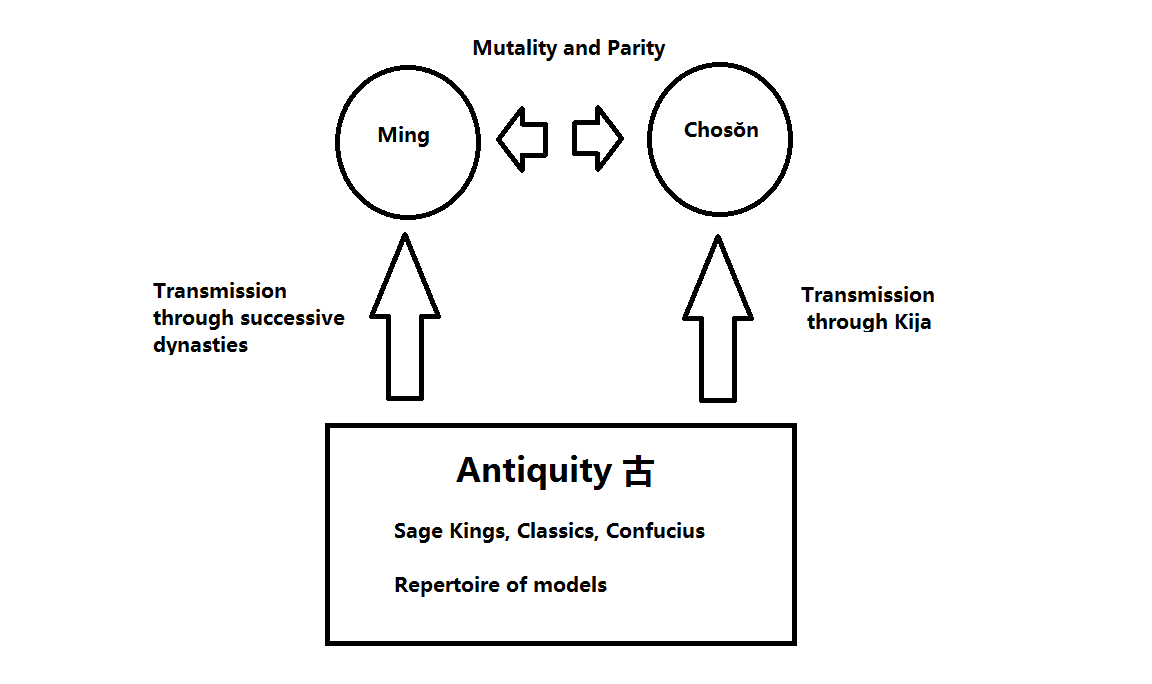

Figure 5: Ming Influence model of the civilizing process

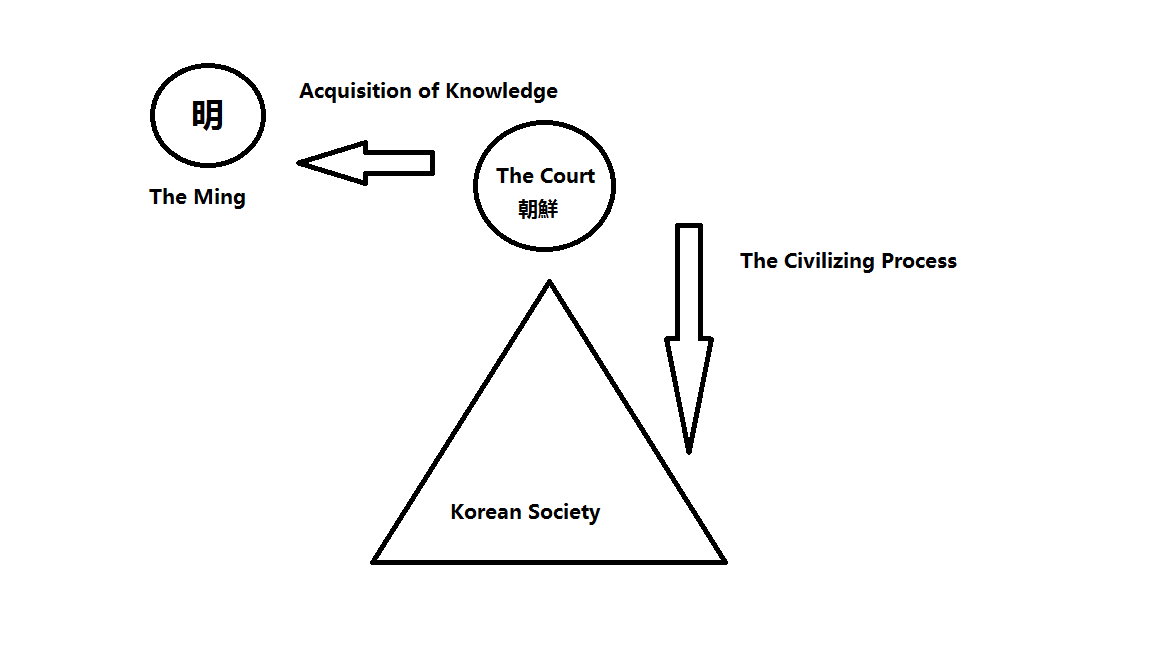

Figure 6: Chosŏn Court-centered model of the civilizing process

Two narratives of the civilizing process: Ming influence (figure 5) and appropriation by the Chosŏn court (Figure 6)

These two narratives, one of "eastward transmission" and another that emphasizes Korea's autonomous civilizing process, appear to be complementary historical explanations. Each narrative reflects a distinct claim of cultural authority, ascribing agency over the civilizing process, and therefore political sovereignty, to different actors. Neither perspective is complete, nor are they mutually exclusive. An exclusive focus on Chosŏn agency may occlude the Ming's role as a transmitter of knowledge and a model for Korean institutions, but understanding this process solely in terms of Ming influence leads to more critical problems. For one, it discounts prior Korean interest in Neo-Confucianism and the classical tradition in general well before the Ming's founding. After all, Ming gifts of books would have been meaningless without a ready audience to receive, interpret, and apply the knowledge they contained. Korean rulers and their subjects did not need Ming exhortation to "read books;" they were doing it already. Korea's civilizing process was not a spontaneous response to imperial virtue. And neither envoys nor emperors were responsible for bringing spring flowers to Korea, even if their poetry suggests otherwise.

The two narratives are thus less complementary than they first appear, because they in fact encapsulate largely incompatible notions of cultural and political authority embedded in their distinct directionality. This tension directly impinges on how the Brilliant Flowers and envoy poetry should be interpreted. Scholar Du Huiyue points to the reaction of Ming literati to Korean envoy poetry. For them, such as the Ming scholar Wu Jie 吳節 (1416--?), who wrote a preface to the Ming envoy Ni Qian's poetry anthology, Korean poetry exchanges were not only "testimonies to Korea's civilization," but also a demonstration of "the success of the Ming dynasty's propagation of civil and Confucian culture to faraway lands."107 To show that Korean writers expressed similar sentiments, Du uses as an example Sŏ Kŏjŏng's preface to the personal collection of poems exchanged with Ming envoys compiled by the Chosŏn official Pak Wŏnhyŏng 朴元亨 (1411--1469). Indeed, Sŏ Kŏjŏng expressed pride over the flourishing of the "ritual, music, and culture of China" (中華禮文化) in Korea. For Du, Sŏ's statements too implicitly confirmed the "success" of the Ming's civilizing project.108 A closer reading of Sŏ's preface, however, shows that Sŏ envisioned the directionality of the civilizing process in ways entirely different from Ming literati like Wu Jie:

Our Eastern Country is situated far beyond the sea. The flourishing of its ritual and music can be compared to that of the Central Efflorescence (i.e. China, chunghwa). There has been no shortage of excellent men who were worthy [of comparison ] to ancient worthies and ministers. The Revered Imperial Ming reigns over the universe. From within the seas and beyond, there are none who are not its subject. It looks to Chosŏn, and treats it as a feudal lord of the interior. With gifts and tribute, [the Chosŏn and Ming ], look to each other.109

Sŏ was certainly proud of the flourishing civilization in Chosŏn, but there is no sense that this civilization was transplanted from the Ming. Instead, Chosŏn, whose men of talent were on par with "ancient worthies," becomes virtually equivalent to China, the Central Efflorescence. Civilization flows not from the Ming per se, but from antiquity. Chosŏn was now coeval with the Ming, at least in terms of its "ritual, music, and literature." In this formulation, trappings of civilization were not inherently "Chinese" or Ming objects, but legacies of a common classical past. In the present they became a benchmark against which civilizational attainments were to be measured. The origin of Chosŏn's civilization was no different from that of the Ming; they flowed from the same wellspring.

Figure 7: Coeval model of the civilizing process

Cultural parity and shared inheritance of the past: a third vision of the civilizing process, understood by Sŏ Kŏjŏng and promoted by the Brilliant flowers

Sŏ acknowledged Ming claims of universal authority, which also implied sovereignty over not only Korea, but all of the ecumenical world. Nevertheless, no causal relationship between Ming universalism and Chosŏn efflorescence was advanced. Instead, they were mutually constitutive. A reciprocative hierarchy allowed the two parties to gaze upon each other with "gifts and tribute." This sense of mutuality and reciprocity, founded on the Ming's (im)partial treatment of Korea is elaborated further in this preface. The way Sŏ emphasized the agency of Korean court officials like himself in fact decentered the Ming, even as its emperor sat at the apex of the world.

Now the Son of Heaven [i.e. the Ming emperor ], benevolent and sagely, [treats ] the four seas as one family. Our Majesty [ever since ] he has bore heaven's [mandate ] and inaugurated his rule, served the Great State with utmost sincerity. Your Excellency assisted [the king ] left and right, a great aid for all times. With your literary refinement and ritual decorum, you acquired a bearing that brought respect to our king. With your chanting of poems and your matching of verses, you glorified the Son of Heaven's court.110

Even though Sŏ's original preface praised the Ming emperor as a "benevolent sage" and celebrates "the four seas as becoming one family," the Ming's civilizing role is conspicuously absent. What follows instead is a delineation of political hierarchy descending from emperor to king to courtier that was couched in a series of linked reciprocities. The Chosŏn king and the Ming emperor complement one another in this vision of political order. And, through the mediation of the talented courtier who "brought respect to our king" and "glory to the Son of Heaven's court," the Ming's benevolent impartiality and the Chosŏn king's dutiful service to the emperor fashion one another.

Sŏ's formulation illustrates a clear alternative to how Ming observers interpreted literary exchange in diplomacy. Here, each element played a vital role in constructing the political order of empire. The Chosŏn king received his own mandate, but in this account, the courtier took center stage. It was the mediating role of the Korean literati courtier---people like Sŏ Kŏjŏng himself and his friend Pak Wŏnhyŏng---who made empire possible.

Sŏ argued that Chosŏn and the Ming derived their civilization from a common wellspring of antiquity. The Ming, as guardians of that tradition, had become the fountainhead of its transmission in the here and now, but it could not prevent the Chosŏn from also claiming a direct, independent avenue of transmission to that classical past.111 Nonetheless, in the context of envoy poetry and other diplomatic writing, that Chosŏn claim had to be attenuated with an acknowledgment of Ming claims as well. Here, Sŏ's description of the Ming treating Korea as a "feudal lord of the interior" (海內諸侯) becomes significant, not so much as a way to express Ming suzerainty, but rather as an evocation of a pre-imperial past, the age of Sage rulers and classical texts.112

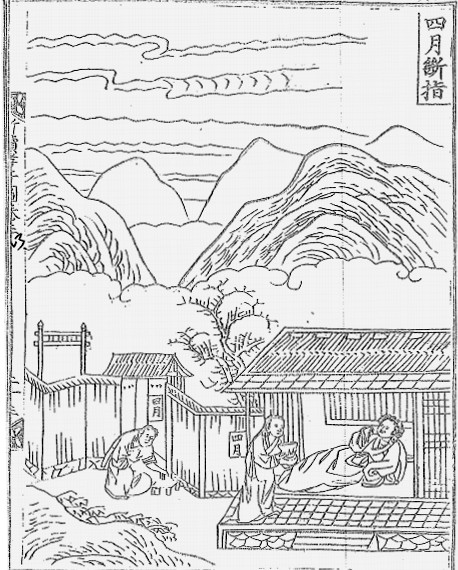

These parallel narratives of "civilization," in terms of Ming influence, of the Chosŏn court's activist efforts, and of Korea's independent cultural transmission from the past, provided the interpretive lens to understand social phenomena. The case of the filial daughter of Kwaksan is illustrative. Ming envoys traveling to Seoul always passed through the town of Kwaksan 郭山 in Pyŏng'an province. There, by the roadside, they saw a stele and memorial gate (chŏngnyŏ 旌閭) erected on the orders of the Chosŏn court in 1422 to honor the memory of a filial daughter named Kim Sawŏl 金四月. Abandoned by her father as a child, Kim lived alone with a mother who suffered from seizures. When she learned that bone and flesh from a living person could heal her mother's afflictions, she cut off her finger and fed it to her mother. Her filial act apparently worked; her mother recovered.113 In 1450, the envoy Ni Qian first took notice of the monuments and dedicated a poem to her. Later Ming envoys and their Chosŏn companions followed suit.114 Chosŏn and Ming envoys were unanimous in their praise of Kim Sawŏl's virtue, but what varied was how this extraordinary act of filial devotion should be explained.

Figure 8: Kim Sawŏl cuts off her finger

"Kim Sawŏl cuts her finger." Depiction of Kim Sawŏl's filial act in the Tongguk sinsok samgang haengsildo 東國新繼三剛行實圖 f.3:21a

From the very beginning of her literary life, the filial daughter became a symbol of the civilizing projects of both the Ming and the Chosŏn courts. To Ni Qian, she testified to the "far extent" of the "civilizing transformation" of successive Ming emperors.115 Ming imperial grace, which "did not distinguish between the civilized and the barbarian"116 made Sawŏl's deeds possible. Ni's respondent, the Chosŏn official Sin Sukchu 申叔舟 (1417--1475) saw the matter differently:

....Our King affirms filial principles; Where there is good he will bring it to light. Praising the beautiful to admonish future men, He carves [these deeds ] in stone to set them apart. To set examples, so that all will have their place, Are memorial doorways, gates and posts. And so, this filial daughter--- Her fragrant name will always be exalted.

Sin Sukchu framed these lines with a celebration of Ming empire, but the agency of elevating Korean customs clearly belonged to the Chosŏn. A filial child like Kim Sawŏl validated the Chosŏn court's concerted effort to encourage Confucian practices, and not the natural consequence of the Ming's imperial influence.117 In emphasizing the act of "exaltation," Sin then inverted the outward and downward impetus of the "civilizing" logic in the Ming envoy's poem. The Chosŏn king had erected these monuments to celebrate the virtue of a commoner. By analogy, the Ming envoy's duty was also to use his privileged position as an imperial ambassador by recognize the success of the civilizing project. He exhorted the Ming envoy to write "poems that uplift customs and virtues," so that "in Korea, for a million and a myriad generations, / A clear wind will blow among the stalwart and righteous ..." (作詩樹風節 三韓億萬世 淸風吹凜烈). Sin centered Chosŏn's royal initiative while limiting the role of the Ming by assigning it only an auxiliary power of vindicating virtue through writing.

Ni and Sin set the stage for later interactions. Other envoys like Gong Yongqing continued to use Kim Sawŏl as an opportunity affirm the success of the Ming's civilizing project. Her actions showed that "imperial airs naturally extend beyond the Nine Reaches / its beneficence has reached the Eastern Vassal to this degree!"118 Ming envoys allowed for the Korean agency in this civilizing process, but usually only as a proxy to the imperial one.119 Ironically, Kim Sawŏl's act of filial devotion was more likely informed by autochthonic religious practices than motivated by Confucian mores, but that did not prevent her from being appropriated by two parallel political projects. The Chosŏn court used her memory in a state project of commemoration, while the Ming saw her as validation of its political imaginary of universal empire.120

How these nestled appropriations were constructed for Kim Sawŏl is a microcosmic analogy for underlying tensions in both the envoy writing of the Brilliant Flowers itself and Chosŏn-Ming diplomacy as a whole. Chosŏn writers reconciled these tensions by elevating them to a different register, tying a common project of literary production to classical models of antiquity. Rather than emphasize Chosŏn's role at the expense of an imperial view, they circumvented the issue by incorporating Chosŏn into the imperial vision in specific ways. The Chosŏn poet-official Yi Haeng 李荇 (1478--1534) wrote:

...Who knew that this one girl, Would alone be collected among the envoy's poems? I heard that Confucius had once upon said "Virtue will certainly have its neighbors" Though [this ] small country is a foreign land, Its people are also of the Imperial House. Its people all devote themselves, To better understand the [Sage ] King's [civilizing ] transformations.121

Declaring that Koreans were also "people .... of the imperial house" was not founded on a desire to become a Ming subject de jure, but an appeal to the universal applicability of classical civilization. The virtuous actions of Kim Sawŏl did become a demonstration of Chosŏn's commitment to the Ming imperium, but did not offer testimony to the Ming's civilizing project per se. The civilizing role of the Sage King, wanghwa (王化), sits ambiguously in the poem, equatable to the moral teachings of antiquity, the civilizing role of the reigning emperor, and the rule of the Chosŏn king. The Ming's civilizing power and Chosŏn's project of Confucianization blended together in a narrative of filiality that synthesized the two visions, obviating the need to claim primacy for one over the other.

The synthesis led to an emphasis on the literary agency of the envoy. Indeed, the envoy and his writings sometimes stole the spotlight that was ostensibly shone on the filial daughter. Yi Haeng hearkened back to Sin Sukchu's response to Ni Qian and offered the following advice to his Ming guests:

The starry chariot has traveled far---where does it go? Its path leads to the Verdant Hills [i.e Korea ] for collecting poems. Sagely Transformation has flowed to the east; every family is virtuous and righteous. Now, there is more than what [you have seen ] on Kwaksan's stele.122

The flow of civilization eastward had achieved astounding success. Kim Sawŏl was not the only virtuous figure in Korea. With examples like her everywhere, the envoy's duty was to "collect poems" and announce to the world her virtue. The envoy by, "troubling himself with a brush to write a poem," could preserve her "fragrant name" for a "thousand ages." In Yi's colleague Chŏng Saryong 鄭士龍 (1491--1570) poem, the envoy writing replaced he physical monument, the stele and memorial gate, as the ultimate testament to her virtue.123

Ming envoys looked to their predecessors when they composed their poems, but wrote always in the presence of their Chosŏn hosts. Whereas Wu Jie and Sŏ Kŏjŏng could center the agency of the Ming envoy and the Chosŏn courtier respectively, free from the gaze of their Chosŏn or Ming counterparts, the poetic practice of the Brilliant Flowers did not offer the luxury of solipsism. The diplomatic space congregated individuals with divergent views and their poetry reveals their coexistence. The writers negotiated the implicit tension between these views by relying on a series of alternating deferrals. By appropriating the filial daughter as a symbol for both the Ming and the Chosŏn's civilizing project, the poems never resolved the question of primacy. They instead converged on the literary project as the ultimate raison d'etre of empire, offering not so much a reconciliation as much as an overwriting.

Reenacting the Past: Tuning the Classical Mode

In writing about the filial daughter, Ming envoys and Chosŏn officials alike appealed to the function of writing as recognition. Such gestures not only foregrounded their own literary activities in diplomatic space, but also couched the significance of envoy literary exchange in the language of antiquity and the classical past. The envoy Xue Tingchong 薛廷寵 (fl. 1532--1539) described his paean to the filial daughter as a "song of a country's customs (Ch: guofeng) collected from a boudoir gate" (國風歌謠采閨門). The term guofeng, evoked the "Airs of the States" section in the Classic of Songs, where the customs of feudal states were collected to reflect their moral condition. Posing as a Zhou emissary who "searched all around," Xue evoked a classical model by comparing his own musings to works collected by the "music officials" of yore. Although the classical model suggested the songs were supposed to be local lyrics, not the writings of the envoy, the function of writing was the same. He was to document the beautiful customs he observed so as to encourage their continued practice.124

The evocation of the Books of Songs lends broader significance to envoy poetry, assigning a purpose to diplomatic exchange that situated it in a politics of moral transformation while making the imperial emissary the central agent in this affair. Xue's interlocutor, the Chosŏn official So Seyang responded with his own articulation of the envoy poem's significance.

...The envoy in one glance gathers the people's customs, For a myriad ages, his writing will be as the seas and mountains. In the East, the principle of filiality has been recorded since antiquity, Ever more that the Sagely Ming now tends the jade candle. The "Cry of Fishhawks" begins: the origin of civilization; Women have their proper behavior and men follow their model. If one wants to present this in detail to the Son of Heaven, Without writing (斯文), with what other means does one describe? If you are to investigate all of the Eastern Kingdom, You will find that is not only Kwaksan that has such sites!125

This appeal to the envoy's professed duties of representation reminded the envoy that Korea, the "East," had always been a place suffused with civilization. Kim Sawŏl was not a recent anomaly. Only by accurately representing these facts could the envoy do justice to the Eastern Kingdom. So's articulation intertwined this appeal with his own evocation of the Books of Songs---by mentioning the "Cry of the Fishawks" (guanjiu 關雎), the first poem of the Airs of the States (Ch: guofeng 國風), but the role of this allusion served an altogether different purpose.126 While the hierarchical implications of this analogy---the Ming as the Zhou, and the Chosŏn as a vassal state---were clear, it also revived the image of the classical, ideal past in the current world, actualized through Korea's own efforts. So Seyang credited the Ming with tending the light of civilization, but it was a civilization that began with the literature of the Book of Songs. In this rendition, the Ming's role was severely curtailed. It was neither the agent of the civilizing process in Korea nor the fountainhead of civilization. The former honor went to the Chosŏn court and the latter belonged to the Sages of antiquity.

Turning to literature as the origin of civilization converted the political relationship between the Chosŏn and the Ming into one that served a purpose larger than the relationship itself. Their activities were to be part and parcel of a grand reenactment of the classical past. In what has been described as "using literature to adorn the state" (munjang hwa guk 文章華國), the literary here circumscribes the political within the moral and the aesthetic, where the literary tasks of the envoy became the express purpose of diplomacy itself.127 The emphasis also shifts from the empire's civilizing function to the envoy's role as a producer of literature. This combination of tropes, the literary resolution to the embedded tension between parallel narratives of the civilizing process and the evocation of classical models, was not unique to the poems of the filial daughter. It also echoed other attempts in the Brilliant Flowers to tie Chosŏn to classical antiquity. Sŏ Kŏjŏng's preface to the 1476 Brilliant Flowers offers a case in point:128

When the Kingly Way flourishes,the Odes and Hymns are composed, and so the traces of perfect rule can thus be investigated. In the past, during the height of the Zhou, the poems of Daming, Huangyi, Yupu, Zaolu129 were enough to elucidate prosperity and beauty and renewed the [literary ] creations of an era. And so, [the Zhou ] employed officials to collect poems, and even the minor [works ] of the Kui and Cao states, were still placed at the end of the Airs of the various feudal states. This only goes to show that poetry ought never be neglected. After all, si-poetry, originated from the reality of one's emotions and sentiments exuding from between exclamations and sighs.130 Among them there are those that [involve ] the higher exhorting those below and those below eulogizing those above. A cultivated gentleman should especially make use of what is relevant to the civilizing of the world and is in accordance to the correctness of the Airs and Odes.131 The Imperial Ming reigns over the world and [its influence ] spreads within and beyond the seas, and none do not become its vassal. We the Chosŏn have received civilizing influence (sŏnggyo/shengjiao) for generations and our poetry, documents, ritual, and music possess the manner of manifest civility from antiquity.132

In this articulation of poetry's indispensability, Sŏ established a series of correspondences. The Ming is analogous to the the Zhou, when the poems of the Book of Songs were composed and collected. The envoys sent from the Ming to the Chosŏn are the poetry collecting officials of the past. Chosŏn is analogous to the feudal states of antiquity, but with one caveat--- while Cao and Kui are insignificant states, Chosŏn maintained a direct link to the classical past, a point significant for understanding the rhetorical power of this preface.

Sŏ invoked the classical paradigm of poetry as expression of authentic sentiment to speak to its ability to reflect the governance of the times. Good poetry emerged from good times---the Ming, overseeing an age of virtue was no exception. The Chosŏn produced good poetry, because it had received "civilizing influences" (sŏnggyo) for generations. The civilizing influence here, again, is ambiguous. It could originate from the Ming, but the deep time the preface evokes, and his assertion that Chosŏn inherited the legacies of antiquity could also mean that the civilizing influence came directly from classics. In this preface, the arrival of these envoys was less an expression of Ming influence, than it was a reiteration of the normative status of classical ideals embodied in their symbolic re-enactment. Explicit evocations of the classical paradigms of the Great Preface of the Book of Songs thus granted diplomacy an ulterior purpose: