Chapter 1

"Eternal the Eastern Fief, Serving the Great with Utmost Sincerity": Diplomatic Memorials and the Imperial Tradition

For over a millennium, Korean rulers regularly presented diplomatic memorials, known as p'yomun, literally "documents of expression" (Ch. biaowen 表文), to the emperors of China. The documents, composed in the ornate style of four-six parallel prose (四六駢文), arrived at the courts of the Tang 唐 (618--907), Liao 遼 (907--1125), Northern Song 北宋 (960--1127), and Jin 金 (1115--1234) emperors. The practice continued through the Mongol-Yuan 蒙元 (1206--1368), the Ming 明 (1368--1644), and the Qing 清 (1644--1911) periods. These documents provided valuable symbolic capital for these rulers, because imperial discourse treated "presenting memorials" as a gesture of "declaring [oneself] a vassal" (Ch. fengbiao chengchen 奉表稱臣), an act of political submission. Dynastic chronicles described the recognition of imperial legitimacy by foreign rulers and local leaders alike in these terms.1

The emperor's court counted on its officials to provide effusive encomia to its virtue, but it could not control the presentation of diplomatic missives from polities beyond its rule. Herein lies a fundamental tension, one which scholars of "traditional Chinese foreign relations" have long pointed out.2 The imperial court desired foreign contact as a demonstration of its superiority, but foreign rulers were not always eager to play the role of a political inferior. In theory, memorial presentation and submission were inseparable; in practice, the two did not always go hand in hand. A so-called memorial of submission from a foreign ruler could intimate rather different notions of relational hierarchy. When the Yamato court of Japan first established ties with the Sui dynasty (隋 581--618), its state letter offended Emperor Yangdi (隋煬帝 r. 569-618) for having greeted him as the "son-of-heaven where the sun sets."3 The potential for diplomatic encounters to challenge its authority gave the imperial court good reason to manipulate such encounters to project an image of power it desired. As the Qianlong emperor (乾隆 r. 1711--1799) famously did for the return of the Torghuts to Qing rule, an emperor could deploy the vast cultural apparatus of the imperial state to portray the arrival of guests from afar as "submission."4 Moments of interaction with those beyond the pale became a site to proclaim desired relational hierarchies.

The desired gestures of submission required foreign contact, but the volatility of such relations presented a challenge to the imperial court. Its frontier officials had incentives to minimize volatility. Mismanaging a border conflict could cost them their career prospects, and even their lives. At times, border officials even manipulated frontier interactions to suit the ideological desires of the imperial court.5 The court's own Translators Institute (Siyiguan 四譯館, or 四夷館), responsible for translating documents from unfamiliar, foreign scripts into literary Chinese, was also complicit in this process of equivocation.6 Translation could ensure that letters conformed to the discursive conventions of imperial rhetoric. Although original documents do not survive from the Ming or earlier, examples of original Burmese, Thai, and Laotian "diplomatic memorials" in Qing archives exhibit this manufactured conformity.7 The messages of such "memorials" were rewritten considerably to avert any possibility of offense. After concluding a war with the Qing, the Burmese ruler addressed the Qing emperor as equals in his original letter, but the translated version exhibits deference coded in the language of "the tributary system."8 What appears on the page in the imperial chronicles need not have matched the intent of the letter-giver or the substance of his missive.

Korea was, in fact, a remarkable exception to the rule. Its documents never had to undergo translation, because its documents were already in the literary language of the imperial court.9 Korean rulers, unlike their counterparts from Japan and Vietnam whose idioms of authority were also legible to the Sinitic imperial tradition and relied on literacy in classical Chinese, seldom infringed on imperial prerogatives.10 Korean rulers portrayed themselves as kings and acknowledged the cosmic authority of the emperor.11

Korean memorial drafters not only wrote in the language of the empire, but also did so with full knowledge of their symbolic significance for the imperial court. This mastery of classical Chinese meant that Korean documents were wrought by Korean hands and were not fictions of imperial conceit manufactured by wily translators; thus they appeared to represent genuine sentiment. With a paper trail of declaring submission for over a millennium, it seems, as imperial accounts often suggested, that Korea was indeed the empire's most "loyal vassal state."12 The apparent confirmation of this long-standing stereotype, however, depends on locating Korean sincerity in literary mastery, a line of reasoning that contains the seeds of its own contradiction. If Korean competence was adequate to the symbolic construction of empire, what prevented a Korean author from manipulating those symbols?

Recognition of Korean literary mastery did lead imperial readers to suspect Korean authors of such manipulation. The first emperor of the Ming dynasty, Taizu (明太祖 r. 1368--1398) once described a memorial written by Yi Sung'in 李崇仁 (1347--1392) as "crafted and pointed in diction"(表辭精切).13 Only a few years later, in 1396, the Ming emperor accused Korean memorial drafters of hiding insults in ornate allusions. Since Korean literati mastered the art of composition, any perceived flaw in diction or rhyme, not to mention suspicious homophones and miswritten characters, alerted to possible irreverence.14 The sincerity of Korean memorials hinged on Korean literary mastery, but the very same mastery of language enabled subversion.

When emperors and their officials scrutinized Korean documents, they were mostly over-reading genuine gestures of friendship, not actual attempts to subvert the imperial order.15 As one Chosŏn official lamented for the 1396 controversy, the emperor was "blowing away hair to look for blemishes," searching for instances of lèse-majesté where none was present.16 Such suspicions, however, were not unwarranted. What was at work was simply not the subversion of petty insults or coded insinuations, but something much more subtle, sophisticated, and powerful. These letters, composed by Korea's most talented writers, interfaced with the literary enterprise of empire to insist on Korea's prerogative in the discursive construction of imperial order. In other words, Korean communications with the imperial court did not so much challenge empire as perform a subtler sort of subversion by shaping and guiding it.

Understanding this process of construction requires resisting the temptation to read the literary devices of the diplomatic memorial as "mere rhetoric." Admittedly repetitive use of consistent themes across time in these texts certainly lends to an air of disconnection from the world beyond the text. Yet, it is precisely this temporal stability and endurance that caution against such a reductive view. For if they were ossified gestures, their stakes, shown both in the enormous energies Korean courts devoted to composing them and their sensitive reception by imperial audiences, become difficult to explain. As Joshua Van Lieu has argued in the only serious treatment of this genre in English to date, the literary devices in these texts possessed an illocutionary force that maintained and reenacted the terms of the relationship. Coined by language theorist J.L. Austin, illocutionary force points to the power of a speech-act that moves either the speaker or the audience to future action, even if such demands are not made explicit in the grammar or diction of the statement.17 Paeans of empire in these memorials spoke of benevolent rule, literary and civil virtue, universal sovereignty, and reciprocity not as fanciful description, but as appeals exhorting action according to these principles. This chapter argues that by investing illoctuionary force in its memorials, the Korean court did not only negotiate with individual imperial regimes. They were framing the terms of empire itself.

The endurance of the diplomatic memorial in Korea as both a genre and practice raises several questions. How should this remarkable continuity across dynastic time be understood? Should the tropes and rhetorical strategies they employ be read in terms of generic qualities or situated in the specific, historical contexts of their composition? As this chapter will show, these texts were in dialogue with both scales of time, situating the moment in relation to the broader imperial tradition.

Fifteenth century Chosŏn court compilations preserved Koryŏ and early Chosŏn memorials. They allow an approach to these questions from the perspective of knowledge production. The memorial was both an object of knowledge and a component of knowledge production, a dual existence that makes explicit the dialogic relationship between the two scales of time. On the one hand, these compilations preserved these memorials as examples of literary and rhetorical expertise so they could be consulted in the future. On the other, the memorials themselves produced a timeless image of Korea for imperial consumption.

Treating the memorial as an object of knowledge makes salient that two features of the genre, its putative "eternity" and the "sincerity" of its expression, were both rhetorical devices of the genre itself. Its "eternity," visible in the memorial's consistent use over a millennium, resonates with its performative use of a rhetoric of timelessness, fashioning Korea's relations with empire into one that transcended dynastic time, and for all intents and purposes, an eternal and therefore inevitable political order. These declarations depended on the memorial's "sincerity." Both its exhortative rhetoric and utility for imperial propaganda rest on the assurance of authentic representation, that the memorial indeed expressed genuine feelings.

These two tropes have featured prominently not only in the memorials themselves, but also in the appraisals of later scholars and observers, who have called Korea imperial China's "model tributary." This stereotyped image itself, however, emerged from Korean self-representation. It was an artifact crafted for the memorial, one element in the grander construct of empire. Eternity and sincerity, far from stable notions, and were by far the qualities most volatile in the genre itself and most suspected in the course of diplomacy. For these very reasons, they were the things their drafters most emphasized.

Diplomatic Memorials: The Genre

By the Chosŏn period, the diplomatic memorial already had a long history in Korea. After the fifteenth century, whenever Chosŏn memorial drafters prepared a new document for an embassy to the Ming, they could consult a repertoire of precedents documented in several compilations. Although superficially similar to Chinese antecedents, their organization in these compilations reveals stark differences from earlier examples. These compilations, as both a reflection of past practices and a guide for future ones, granted the Korean memorial a stability of genre and form and codified the diplomatic memorial as an object of knowledge.

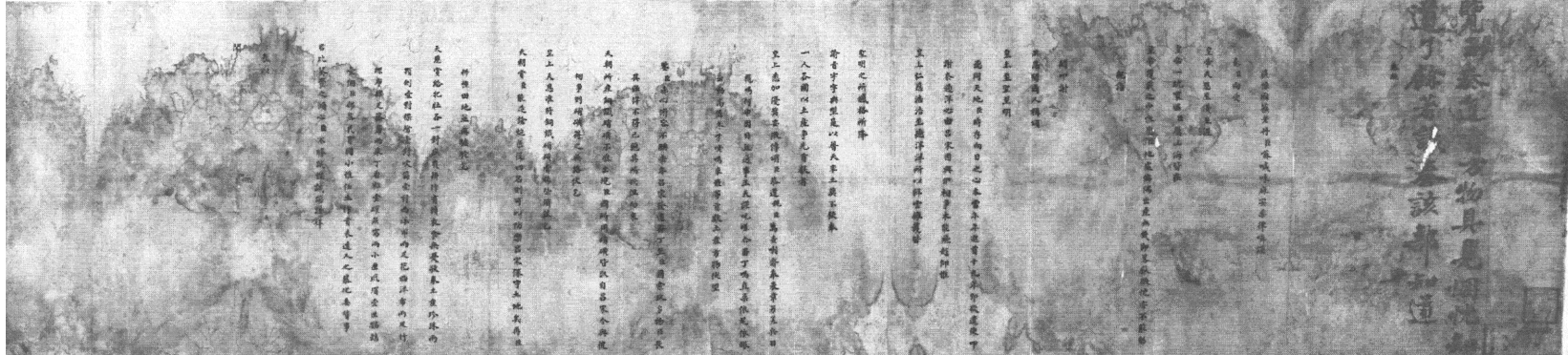

The Chosŏn court and its offices compiled diplomatic memorials as part of other projects. The Chosŏn Office of Diplomatic Correspondence18 kept copies of past memorials in the Recorded Notes of the Pagoda Tree Hall (Kwewŏn tŭngnok 槐院謄錄), a selected collation of the bureau's documents.19 Various dynastic histories provided scattered examples antedating the Chosŏn. Court officials gathered these documents in one place when they included them a larger compilation, the Literary Selections of the East (Tongmunsŏn 東文選) in the middle of the fifteenth century.20 This anthology also collected a range of other diplomatic epistles, such as official rescripts to imperial agencies (as opposed to memorials to the emperor) and personal letters from Korean rulers to imperial officials in addition to p'yomun. The documentary record of pre-Chosŏn Korean diplomacy largely owes their survival to these fifteenth-century compilations.21

The name, Literary Selections of the East, echoed that of the anthology compiled by the Liang (梁 502--557) prince Xiao Tong 蕭統 (501-530), The Literary Selections (Wenxuan 文選). The compilers of the Korean anthology deliberately hearkened back to the older title as way of creating a literary canon of the "East" (i.e. Korea) that was not only distinct from, but also on par with that of China. One of the leading compilers and the preface writer for the anthology, the Chosŏn official Sŏ Kŏjŏng 徐居正 (1420--1488), wrote that it collected "neither the literature (mun 文) of the Song and Yuan nor the literature of the Han and Tang, but the literature of Our country." The compilation finally "place[d] it on alongside the literature of the ages," so that it could be transmitted to posterity.22

Xiao's Selections and the Chosŏn Selections of the East share organizational similarities. Both offer a comprehensive view of literary genres and styles. The Selections of the East also reproduced Xiao's order, maintaining the precedence accorded to poetry over prose. It treated differently the two classical generic categories to which the diplomatic memorial belonged, the biao (Kr: p'yo 表) and the jian (Kr: chŏn 箋).23 Whereas Xiao Tong only included three examples of biao and jian in total, a minuscule proportion of the entire collection, p'yo and chŏn together occupy fourteen out of one-hundred and thirty fascicles (roughly one-tenth) of the Korean anthology. The shared nomenclature of Korean memorials and the Chinese genre is misleading, for these documents of the same name had an entirely different existence in Korea.

The Korean p'yojŏn, like the classical biao and jian, addressed rulers. In the Ming context, the former was used for personal correspondences with the emperor while the latter addressed other members of the imperial family. They were reserved only for highly formal occasions and became formulaic as conventional documents of congratulations by the late imperial period.24 The Chosŏn king also presented such documents for imperial celebrations. The Selections of the East include memorials presenting felicitations to emperors on the New Year (hajŏng p'yo 賀正表) or other important ritual events such as the investiture of a crown prince or empress.25 These celebratory memorials could also address specific events, such as the successful conclusion of an imperial military campaign.26 Memorials such as these, written for specific occasions are thus more varied in content and can often be found in other sources, such as the literary anthologies of their authors or official histories. Korean letters also expressed gratitude for imperial gifts (saŭn p'yo 謝恩表). These, and the "expression memorial" (chinchŏngp'yo 陳情表) or the "request memorial" (chuch'ŏng p'yo 奏請表), tended to be less formulaic because they usually addressed specific diplomatic issues.27

The nomenclature gives no hint of their function as diplomatic documents, since memorials by the same name could also be presented by the Ming officials and nobility.28 At work was a conceptual framework of political hierarchy distinct from that which bound a Ming official to his emperor. Korean monarchs ruled a domain beyond de facto imperial control, a distinction carefully preserved in the language of these memorials. They represented the Korean ruler as the master of his own people (min 民), ancestral shrines (chongmyo 宗廟) and altars of state and grain (sajik 社稷). Nevertheless, by reserving p'yo for the emperor, Koryŏ and Chosŏn monarchs deferred to Yuan or Ming rulers as universal, cosmic rulers. This arrangement placed the Korean ruler on par with imperial officials; both were imperial subjects (sin/chen 臣). Korean rulers, by receiving only chŏn from their own subjects, occupied a position of parity with imperial princes, consistent with their treatment in Ming ritual hierarchy.29

Here we have a tension between two competing and overlapping operative logics. From the vantage of the Ming court, Korean memorial presentation was a ritual practice legible to the integrative logic of imperial rule, as it was coherent and compatible with its own institutions. This logic obliterated any distinction between what was "internal" (nae/nei 內) and "external" (oe/wai 外) as the Chosŏn monarch and his kingdom were but one of many such entities in the imperial fold. The other, from the perspective of the Korean court, was their diplomatic function. These memorials represented Korea as a state to an outside power.30 These two modes, in practice, worked together; the rhetoric of any given memorial had to satisfy both sets of demands.

The organization of the Selections of the East reflects an attention to rhetorical function. The compilers arranged the letters first according to occasion, before arraying them in chronological order. Attention to discursive function, highlighting rhetorical form and style thus superseded historicist concerns, reflecting the decidedly literary emphasis of the anthology. The Selections of the East could thus provide convenient models for future composers.

The anthology did not just provide models for diplomatic missives. Early Koryŏ period memorials did not always formally distinguish Korean rulers from their erstwhile overlords, the Liao, Jin, and Song emperors.31 From the fourteenth century onward, during the period of Mongol domination, Koryŏ officials no longer addressed their own monarchs with p'yo, but only with chŏn, a reflection of the Korean monarchy's demoted status vis-a-vis their imperial suzerains.32 Taxonomic distinctions notwithstanding, these documents differed little in form and style either from diplomatic missives or their earlier Koryŏ predecessors. Modes of imperial adulation easily transferred to Korean rulers and vice versa. Although chŏn carefully avoided obvious imperial titles, the rhetorical paraphernalia of Korean kingship did violate imperial prerogatives. One early Chosŏn memorial, for instance, lauded the Korean king for "succeeding heaven's [mandate] and ascending to a supreme [position]," and "inaugurating [his own] inheritance of a new august throne" (繼天立極 誕膺景祚之新) in celebration of a royal sacrifice.33 The "august throne" (景祚), "heaven's [mandate]" and the "supreme position" were unmistakably imperial pretensions.34 Chosŏn memorial writers used such turns of phrase liberally to describe the Ming emperor in diplomatic memorials, but described the Korean ruler in these terms only in documents for domestic consumption.

The legitimation of rulership in both the Chosŏn and the Ming relied on a common classical idiom, so the lexical overlap comes as no surprise. Another Korean memorial, for example, celebrated the Chosŏn king's fulfillment of "the lessons of the Great Plan [of Yu]" (講洪範之訓辭), the same classical text that was the foundation of both classical rulership and provided the link to antiquity required for imperial legitimacy.35 A congratulatory memorial for a royal birthday traced the Korean king's legitimacy to his personal virtue and heaven's will, manifested in his "careful devotion to the emperor" (小心於事帝) and his "dutiful observance of envoy missions" to China (叨領使華). Even so, all this was nested in his "reverence of Tang dynasty's models" (慕唐朝之典) and "sharing the ceremonies of the Han palace" (同漢殿之儀). Even as these domestic memorials avoided challenging imperial authority, and acknowledged its superiority, they nonetheless appealed to the models of legitimate monarchy offered by a common imperial tradition. The drafters of these memorials walked a narrow tightrope between an appealing to a shared tradition and infringing on imperial prerogatives.36

Inheriting a shared political tradition did not automatically translate into good relations, because it also implied rival claims on an imperial transmission that was in theory indivisible. In the Koryŏ period, one Yuan official who visited the Korean court protested how similar its ceremonies, "the grand meetings, royal canopies, dragon screens, and retinues," were to those of the emperor's court. Officials even called aloud to wish the ruler long-life and performed kowtows, which he declared a "gross usurpation" of imperial prerogatives.37 Cognizant of these issues, the Chosŏn court deigned to share with Ming envoys the details of its government institutions, for fear that similarity to Ming ones would be taken as an affront to the imperial court.38

Korean diplomatic memorials, thus mutually constitutive and ideologically interdependent with their domestic counterparts, point to a larger set of issues. Together they are part of a broader story of appropriation, in which Korean statecraft had long adapted imperial practices. The institutional parallels that emerged of which the use (of the memorial is only one example) fostered legibility between Korean and imperial practices, but it also meant Korean claims of authority were always in implicit contest with imperial ones. The avoidance of obvious affronts to imperial claims, such as the use of a separate calendar, illustrates the delicateness of diplomatic representation. That Korean rulers and their officials tailored their correspondences in this manner demands acknowledging the strong possibility for deliberate representation in such political performances and cautions against reading them simply as genuine expressions of some general truth about the nature of Chosŏn-Ming relations. Diplomatic memorials, p'yomun, cannot be taken literally as transparent "documents of expression."

The crux of the matter is a tension between competing sovereign claims. How does the diplomatic memorial manage this tension? Addressing this question requires examining the diplomatic memorial as a genre diachronically. The memorial bound Korea to the imperial tradition, and so its history must be understood in conjunction with the history of empire.

A Genealogy of Empire

Compilations like the Literary Selections of the East gave diplomatic memorials a generic coherence, constructed through their accumulation of tangible examples. Their compilers transformed a repository of inert documents by bringing them together collectively as a device of knowledge. Through them, the rhetorical strategies for engaging with empire became a craft that could be mastered. Reading diplomatic memorials as a form of knowledge is crucial to understanding their significance in Korean diplomacy. In his preface to the Selections of the East, Sŏ Kŏjŏng writes the following of Korea's literary achievement.

When the [Northern and Southern] Song contended with the Liao and Jin, [we] avoided national calamity over and over by dint of literary writing. In the time of the Yuan, [our scholars] arrived as foreign guests in their civil service exams and met as equals the talented men of the Central Plains [i.e. China].39

The first achievement was strategic. Sŏ credited memorials and other diplomatic missives for saving Korea from destruction during times of upheaval, a time period where multiple contenders and claimed imperial status. The second accomplishment was its ability to demonstrate cultural parity with China. This second claim did not address diplomatic writing per se, but its assertion of cultural parity was ultimately inseparable from Korea's strategic encoding of its relations with empire.

The Literary Selections of the East was not an inert repository. At the outset, it was a result of a selective rendering of a genre. Its compilers had culled a particular set of documents from extant materials. Although they predated the Chosŏn, these texts were meant to inform later compositions, so they are as much objects of the Chosŏn as they are of earlier historical moments. Their retrospective accounting of Korea's interactions with past empires also offers a genealogical reading of the past, a window into its compilers' understanding of how Korea's history had come to constitute the Chosŏn present. The immediate task here then is to read "along the grain," to discover the strategic work they were intended to do.40

Although a form of encomium, the diplomatic memorial was appropriated for strategic use from its inception. The earliest examples were not congratulatory memorials or declarations of fealty, but missives that sought to enlist imperial authority and commandeer its power. One, sent by the P'aekche (百濟 trad. 18 BCE--660 CE) ruler to the Northern Wei (北魏 386--534) emperor, was a request for military aid, hoping to draw imperial intervention against the rival kingdom of Koguryŏ (高句麗).41 Another, sent by the Silla for Tang Gaozong (唐高宗 r. 628--683), was the memorial that spurred on the Tang invasions of P'aekche, which precipitated the unification of the Korean peninsula under Silla.42 Although these early memorials adopted the language of vassalage, they were not unequivocal paeans to imperial power. They were instead tools designed by their anonymous composers who used them to glorify imperial power only to turn it to their own ends.

The diplomatic memorial appears as a bona fide genre only with the work of the Silla literatus Ch'oe Ch'iwŏn 崔致遠 (857--951), whom Sŏ credited as the "originator of Korea's literary tradition" (吾東方文章之本始也). Ch'oe's life was in many ways a shorthand for the cultural dynamics of appropriation between the peninsula and the continent at the time. He was a representative example of the many individuals who traveled west to China and returned home with the fruits of their experience.43 Ch'oe left Silla at a young age for the Tang capital Chang'an to pursue his studies. There, he passed the civil service examinations and served as a Tang official until he returned to Silla in 884.44 In his homeland he promoted literary Chinese and argued in particular for the importance of literary craft to the conduct of diplomacy.45 He applied his craft in this capacity, as the the first diplomatic memorial to receive an attribution of authorship in the Selections of the East was one Ch'oe wrote to present felicitations to the Tang court.46

After a long period of selective appropriation, elements of Tang court practice had become an established part of Korea's cultural landscape. The use of the p'yo-memorial in diplomacy was no exception. The majority of the extant documents date from the Koryŏ period, though a significant portion are from after the Mongol invasions.47 The pre-Mongol memorials addressed the Liao, Jin, and Song courts, who all claimed to be legitimate successors of the Tang's once unified empire by adapting and reinventing its ritual and rhetorical technologies in the process.48 Rival claimants to unified empire competed for Koryŏ's recognition. In the meantime, as Michael C. Rogers described it, Koryŏ relied on "its considerable diplomatic skills, with a keen awareness of the distinction between rhetoric and reality" as it negotiated with these three courts at different junctures in the "post universalistic world" after the Tang's demise.49 The use of the p'yo-memorial, then, was a signature practice of Korean diplomacy; just as no one emperor monopolized the imperial tradition, no one imperial dynasty exclusively enjoyed Koryŏ's tribute missions or its declarations of fealty. These documents are poignant reminders that the imperial tradition was not coterminous with an ethnocentric idea of "China." For the greater duration of this period, Koryŏ sent these memorials, not to the Chinese-ruled Song, but to the "multiethnic" empires of the Khitan Liao and the Jurchen Jin.50 The "diplomatic memorial" and the practices surrounding it developed through a line of dynastic transmission that mainly circumvented the Song, and passed through the northern dynasties of the Liao and Jin, and finally to be inherited by the Mongol Yuan.51

In this context, a Korean diplomatic memorial acquired additional symbolic importance for these rival imperial states. Korean envoys bearing these missives arrived at least annually to the Liao and Jin courts, but their presence in the Song was a rare cause for celebration. The reign of Emperor Huizong (徽宗 r. 1100--1126) saw a flurry of renewed diplomatic activity with Koryŏ. Huizong, hoping to isolate the Khitan Liao who had occupied the "lost" sixteen prefectures in northern China for generations, sought to kindle an alliance with the Koryŏ against them.52

The Song court celebrated the arrival of Koryŏ embassies by holding special civil service examinations for the Erudite Degree,53 where examinees wrote mock diplomatic memorials in the voice of the Koryŏ king. Huizong held one such examination in 1114. On this occasion, examinees wrote as the Koryŏ king showing thanks for a bestowal of musical instruments.54 Why the Song asked its examinees to write in the voice of the Koryŏ king requires explanation. The test could have measured literary versatility, a desirable quality for a court composer. Since the Song court dispatched diplomatic letters of its own to rival imperial states, a mock Koryŏ letter could have also served as a model. Or, it could have been a template for "translating" letters from other foreigners into a language suitable for presentation to an imperial audience.Perhaps the rhetorical niceties considered appropriate to this context could be recycled to suit the ideological needs of the court. Regardless of their purpose, comparing these mock memorials to actual Korean memorials reveal stark differences. It amounts to the difference between an imperial fantasy's clichéd projection of what a Koryŏ memorial should be and what an actual Koryŏ strategy of self-representation was. Korean memorials defied these imperial expectations, but they also exceeded them. They offered something far more valuable than what the imperial court initially hoped for, but not before claiming a piece of the imperial tradition for themselves.

The top examination passer for the 1114 Erudite exams was Sun Di 孫覿 (1081--1169). The editor of the Southern Song Compass to Composition (Cixue zhinan 詞學指南), Wang Yingling (王應麟 1223--1296) found Sun's response worthy of inclusion as a model essay.55 He lauded Sun's essay for its effective use of diction:

If in the opening phrases, one spoke only words such as "favor extending to distant countries," like a second-rate writer would, it would be weak and without power. And so, [Sun Di] took the meaning of these words and transformed them. [The phrases] "[You] granted the letters [of investiture] and for a myriad leagues culture is all unified" are what [I mean]. One has only to read these two phrases to see the big picture.56

The structure of the essay was equally important:

He first speaks of how the distant barbarians are not worthy enough to know elegant music and then narrates the splendor of the musical performance and the favor of bestowal. One can use this as a model for any memorial [expressing thanks] for receiving gifts as one of the four barbarians.57

The memorial not only proclaimed the universal claims of imperial rule, but also demonstrated the humility of the "barbarian" ruler, who once ignorant of civilized ways, was now basking in the transforming glory of "elegant music." Weaving these tropes together with appropriate classical allusions in the proper parallel prose made for a good memorial.58

Huizong may have been thinking of the Dashengyue (大晟樂) when he held the special round of civil service exams in 1114. Completed in 1105, the Dashengyue project was a new repertoire of court ceremonial music designed to restore the musical standards of the Sage Kings. The creation of the new music coincided with other cultural and political projects that meant to augment the prestige of the Song imperial house. In this period of renewed imperial activism, the Dashengyue was thus intimately connected with an irredentist war against the Khitan Liao, which ultimately precipitated the Northern Song's destruction.59 When Huizong bequeathed the instruments and scores of his new music to Koryŏ in 1116,60 he also made relations with Koryŏ an integral element in the plan to restore Song imperial splendor.61

One need only read the actual Koryŏ letter Huizong received to see how different it was from the mock memorial. The actual Koryŏ letter thanking Huizong for this gift of music differed in essential ways from the Song mock memorial, matching neither its structure nor its rhetorical flow. Instead of humble barbarians professing their ignorance in the face of the civilizing imperial knowledge of Song, we find the following:

Your Servant has heard that when Xuanyuan [the Yellow Thearch, Huangdi] created the Xianchi and Yu [the Sage King] completed the Daxia, they used their own body for their measures and forged tripods to test their sounds.62 Before the Zhou, all followed their rules. [Those] from the Han on failed in their transmission. The [corrupt sounds] of the Zheng and Wei burgeoned, and the Airs and Elegantiae [i.e. the proper music of the Book of Songs] were long broken.63 The various scholars could not construct them, and the generations that followed could not develop them. [But] the Way was not enacted in vain, and Principle had something to it. Now, Your Majesty the Emperor, wise and sagely, brilliant through sincerity, took up the remonstrance of recluses, absolved the confusion of measurements, and followed the legacy of the ancient kings. And so, [You] achieved the balance of the Yellow Bell,64 adorning it with the five modes, disseminating it in the eight instruments. Promulgating them in the altars and shrines, the various spirits submit; and proclaiming them in the imperial court, the commoners and officials are harmonious. [With this you] illuminated the achievements of an age, and revived the fallen paragons of antiquity.65

The Koryŏ letter exhibited a mastery of classical diction and rhymeprose equal to that of the Song court composer. This mastery allowed the Koryŏ to represent its own interpretation of the Dashengyue as a project of cultural revival. No less an encomium to imperial virtue, praises of Huizong for matching the achievements of sage rulers show that the Koryŏ recipient could appreciate as a connoisseur and not as a mere consumer. He is not simply overawed by the music's splendor, but can hear the resonances of its classical tunes. He recognized its accomplishment because he was not an ignorant barbarian, but a cultivated listener knowledgeable of the classical past. Their culture hailing from the same tradition, the Koryŏ approached the Song as cultural equals.

The letter amplified the cultural significance of Huizong project, but did so while underscoring Koryŏ's qualifications as a participant in this project. The letter closes with the assurance that with "the enduring echoes of the bells and chimes," the Koryŏ too will "use the ocarina and flute to set straight the sounds," and replicate the musical standards the Song promulgated. By participating jointly in the spread of the Dashengyue, the Koryŏ well help bring "great peace that flows in unison with heaven and earth" for "transmissions [lasting] a hundred generations," and celebrate the "mutual joy of ruler and subject."66 Koryŏ was not grateful for this piece of Song civilization, but to the Song for contributing to the civilizing project as a whole.

The Koryŏ letter also exceeded Song expectations for praise, even where it echoed them. The actual and mock memorials did share some features. Phrases such as "flowing in unison with heaven and earth" (天地同流) and "the mutual joy of ruler and subject" (君臣相悅) find their way into both. Since both Song and Koryŏ writers drew from a common classical repertoire, identical allusions were sometimes unavoidable. In this case, a passage in the Mencius that saw harmonious resonance between the human and natural worlds to parallel good relations between ruler and subject served as an apt referent.67

Indeed, the revival of ancient music was also to produce these harmonious correspondences. Ritually correct music could not only regulate the empire, but also acquire the cooperation of barbarian peoples and supernatural beings alike. To this effect, Sun Di likened imperial music to the "the dance of shields" performed by the sage ruler Shun 舜. In its locus classicus, the "Counsels of Great Yu," the dance represented the ruler's moral influence, which succeeded in moving his enemies, the Miao barbarians, to "submit after seventy days."68 The Koryŏ memorial alluded to the same passage and adapted it to the wording of Huizong promulgation of the Dashengyue. Though the Song edict only described the performance of this music as a way to "honor the deities and spirits," the Koryŏ memorial claimed that the performance of music brought even "spirits to submission."69 Here, we have a correspondence not of emotional resonance, but of literary fashioning. By acknowledging Song claims in writing, the Koryŏ achieved the same sonorous harmony sagely music was to achieve. Like musical harmony, both correspondences in text and in diplomatic practice required mutual action for their effect.

The resulting intertextual harmony was not a spontaneous response to the moral virtue of the Song. Even though both the mock and actual memorials referred to the power of music as moral influence, the harmony of both text and action resulted from deliberate orchestration, as both the Koryŏ and the Song worked together to construct Huizong's sagely image. The question remains whether such orchestrations occurred at the behest of the imperial court or if Koryŏ had responded to the Song on its own terms. Behind these issues is a tension fundamental to this genre. On one hand rested imperial desire to control these representations and on the other lay the need to preserve Korean agency, because only "spontaneous" (read: not coerced) responses could serve as adequate testimony to imperial virtue.

By using mock memorials in its civil service examinations, the Song showed its interest in establishing norms and expectations for this genre of writing. The intended audience of these exemplary exam answers was not likely the Koryŏ court. Thousands of leagues away, the Koryŏ produced a memorial with stark deviations from Song expectations. Furthermore, Koryŏ court composers had their own models to consult. During this period, Koryŏ's court composers had already honed their rhetorical craft in their dealings with the Liao court. By Huizong's reign, the Song were interlopers in a preexisting tradition, one that for over a century the Koryŏ had developed with the Liao without Song participation.

Korean memorial writers anticipated the imperial gaze, ever cognizant of the symbolic value these memorial presentations had for the imperial court. Emperors expressed their displeasure, if a Korean memorial did not somehow fit their expectations. Sŏ Kŏjŏng noted, for example, a Jin emperor who thought that a classical allusion in a Koryŏ memorial had insinuated the less-than-glorious way in which he came to the throne.70 Yuan regulations prohibited certain words from such memorials. Such a rule was intended for Yuan officials, but it also applied to memorials from the Koryŏ court.71 Most famously, the Ming founder, the Hongwu emperor (Taizu 明太祖 r. 1368--1398), prohibited words that reminded him of his humble past. Scholars who violated these regulations were severely punished, including Korean memorial drafters.72 The early Ming "memorial incidents" (p'yochŏn sagŏn 表箋事件) caused considerable consternation at the Chosŏn court and led to the detainment, exile, and execution of Korean ambassadors.73 Amid all this, the Chosŏn court still insisted on sending these memorials, even after the Ming emperor had demanded it desist.74

Ming Taizu's intervention in the matter of diction and literary craft, however dramatic, was unusual.75 Later Ming emperors and officials mostly lauded Korean memorials for their prose and diction. The Yongle emperor was said to have "sighed in praise without end" after reading Korean memorials.76 The Ming grand secretary Yan Song 嚴嵩 (1480--1567) once compared Korean missives favorably to other "memorials from the four quarters," which he dismissed collectively as "inappropriately worded for the most part." Literary mastery allowed the Korean memorial to navigate the rhetorical fine line between vague platitudes and indecorousness. The memorial that impressed Yan Song had "congratulated" the Jiajing emperor for narrowly escaping an assassination attempt by his palace ladies. Yan praised it for managing to avoid "[laying] bare the details of the matter," while still preserving "the facts" of the matter, thus balancing the demands of decorum without losing a sense of relevance.77 To gain recognition as pieces of "literary" writing and its style already required a through expertise, but the requisite knowledge for writing these memorials went beyond conventions, tropes, and prosody. It required a mastery of rhetorical strategies and, most of all, an understanding of the political concerns of its audience.

Despite their visibility as a genre in the Selections of the East, neither the memorials' literary quality nor the rhetorical strategies they embed have been substantively addressed in existing scholarship. Its diction has seldom been addressed beyond its symbolic significance as a gesture of submission.78 Neither do these texts enter literary histories.79 The lack of attention to their literary quality is perhaps a result of a combination of factors. Their explicit ceremonial use makes their rhetorical goals seemingly self-evident, while their highly allusive rococo prose seems to serve nothing more than to ornament straightforward messages of political fealty and praise. The importance Sŏ Kŏjŏng and other early Chosŏn scholar-officials placed on the genre and its prominence in the Literary Selections of the East, however, should alert us to the inadequacy of dismissing them as mere rhetoric. At the very least, their inclusion in a literary canon signifies their importance for a fifteenth-century Korean world-view that has yet to be properly appreciated. This monumental task is beyond the scope of this chapter; what instead follows is a deconstruction of two central rhetorical tropes in all these memorials: sincerity---that Koreans were genuinely loyal to the empire, and eternity---that they would always be so.

Constructing Authenticity: Sincerity and the Imperializing Mode

At the Ming court, the symbolic significance of the Korean memorials depended on their sincerity. The Ming court mandated the presentation of congratulatory memorials (hebiao 賀表) from its officials for imperial birthdays and other important occasions. They could not have directly coerced foreign groups, such as the Koreans, Vietnamese, Ryūkyūans and the like, to do so.80 For one winter solstice in 1543, the Ming Jiajing emperor (嘉靖 1521--1567) expressed his dismay that very few foreign rulers sent their felicitations. The emperor lauded Chosŏn for being one among the few. He also asked the Ming Board of Rites to "encourage" the Chosŏn ruler to come to the Ming to pay his personal respects, which the Chosŏn refused.81 The imperial court could not control memorial presentations or their contents, but it was precisely that lack of control that granted them symbolic power. Couched in a rhetoric of sincerity, these letters were supposed to express spontaneous, willing submission. Autonomous acknowledgment of imperial authority thereby demonstrated its moral attraction. All hinged on the letter's lyrical authenticity--- that is to say whether the emotions they expressed were genuine.

For a memorial to be "sincere" (sŏng/cheng 誠) did not only mean that the sentiments were genuine. In a ritualized context, what authenticated these sentiments was the regularity and consistency of their performance. In other words, the reliability of performance was in itself a demonstration of its sincerity. Therefore, that a particular sentiment was deliberately performed did not necessarily gainsay its authenticity. Moreover, the transformative power ascribed to ritual performance in premodern East Asian ritual thinking meant that repeated demonstration on its own had the potential to alter even disingenuous sentiments. Ritual was supposed to be performative, in that the repeated performance of sentiments also transformed the performer.

However, this also means those who performed rituals were also aware of their performative power and could use them strategically. Repeated performance of ritual, then, could be the very mechanism the performer used to show his audience that he had indeed been transformed in the manner desired by his audience.82 The literary and ritual demonstration of sincerity in the diplomatic memorial itself could thus be a site of potential intercession. Korean diplomats and memorial writers used a rhetoric of sentimental authenticity and performed ritual consistency to construct sincerity as a central tenet of Korean diplomacy for an imperial audience. In doing so, they brought their gestures of sincere submission into a moral economy of empire that exhorted imperial action in terms of principled obligations.

Memorials invariably assumed the voice of the Korean ruler. As missives from the Korean king to the emperor, these documents were to express the authentic sentiments of an embodied sovereignty: kingship personified as an incarnation of a state and its people. The irony was that it was always a fictive, disembodied royal voice. A Korean king never wrote these letters himself; the task of fashioning his royal voice for the imperial ear fell on his court composers. Whereas historical records rarely include names of memorial drafters, treating them as state level communications, both the Literary Selections of the East and the Recorded Notes of the Pagoda Tree Hall ascribe authorship to specific individuals.83 These included the foremost literary officials of the day. From the period of the Mongol invasions until the early 1400s, memorial writers included figures such as Yi Kyubo 李奎報 (1168--1241), Kim Ku 金坵 (1211--1278), Yi Chehyŏn 李齊賢 (1297--1367), Yi Kok 李榖 (1298--1351) and his son Yi Saek 李穡 (1328--1396), Yi Sung'in 李崇仁 (1347--1392), Chŏng Tojŏn 鄭道傳 (1342-1398), and Kwŏn Kŭn 權近 (1352--1409), each of whom was a significant literary and political figure of his day.84

The writers listed above were certainly involved in crafting these memorials, but wordsmithing was only one step in a longer chain of production. Any one diplomatic memorial passed through many hands before a final version was approved for delivery. Chosŏn institutional texts describe an extensive review process.85 Differing versions of the same memorial in different sources suggest an extensive process of drafting and revision, confirmed also by such discussions in court annals.86 In 1396, the first Ming emperor, offended by turns of phrase in a Korean memorial, demanded the extradition of Chŏng Tojŏn, who was reputed to be the drafter. The Chosŏn court replied, undoubtedly to protect Chŏng, that the memorial was in fact wrought by several other officials. As the affair escalated, functionaries, scribes, and other Chosŏn officials came to be implicated.87 Since authorship was not always clear, responsibility was likewise diffused. Authorship was thus in the end just as much as a manufactured effect as the document's disembodied sovereign voice. Together they occluded an entire institutional complex behind their production.

Drafting the text of the memorial was only the first step in preparation. The materiality of the text was equally important and obeyed set conventions by the fifteenth century. The memorial would be written on specially prepared "memorial paper" (箋紙). Officials known for their calligraphy were selected for transcribing text.88 They wrote in thin characters and light ink with references to the emperor and the imperial state elevated to show their superiority, political hierarchies were made explicit in the form of the document.89 The imprint of the Chosŏn king's royal seal (Chosŏn gukwang chi in 朝鮮國王之印), a gift from the imperial court, would be stamped on the paper to demonstrate its authenticity.90 The document had to be in fixed dimensions, at 7.5 ch'on wide and 2.6 ch'on high, with space for twenty characters per column. Finally, the document would be placed in a case of precise specifications. Once sealed inside, the document remained in the container until its presentation to the emperor.91 These elaborate practices functioned both to authenticate the document as a genuine representation of the Korean court's intentions and to ensure their reliability through an establishment of consistent protocols.92

At the heart of these practices was a process of self-construction, but one deliberately tailored for imperial consumption. Conscious of the artifice inherent in the production of such a document, its drafters paid particular attention to the problems of authenticity. They deployed a discourse of sincerity in the diction and rhetoric of these diplomatic documents. Chosŏn memorials described diplomacy with the Ming as the Korean ruler "serving the greater with utmost sincerity" (至誠事大). Viewed this way, memorials were simply a way to express a "sincere [will] to pray [for the emperor's] fortune" (禱祝之誠).93 Such rhetoric suggests the genuineness of Korea's submission, evinced also by the regular, repeated presentation of tribute and the explicit declarations of loyalty, assuring its desire was rooted in authentic sentiment. Sincere submission was in turn supposed to be an unequivocal demonstration of the naturalness and legitimacy of the empire itself. To take only such a view, however, would be to play into the discursive constructs of the Korean memorial. The insistence on sincerity in these documents may have indeed mirrored actual sentiments in certain instances, but it was also a rhetorical tactic of the Korean memorial writer.

The diplomatic memorial was forged precisely in a context where sincerity could not be taken for granted. In a period of political fragmentation, the Koryŏ treated the Liao, Song, and Jin in turn (and often simultaneously) as universal sovereigns. When the Mongol invasions devastated northeast Asia in the early thirteenth century, the Koryŏ court again used diplomacy to make peace with the ascendant Mongol empire. A lasting peace eluded both parties; harsh Mongol terms proved unacceptable to the Koryŏ court, which reneged on earlier agreements once Mongol troops withdrew. When the Koryŏ offered submission to stave off Mongol aggression in 1238, the Mongols questioned the sincerity of Koryŏ's overture.94

These suspicions were well placed. The Koryŏ court was not ready to capitulate. In 1233, it had sent an envoy bearing a memorial to the Jurchen Jin court in Kaifeng. The Koryŏ hoped that a rekindled alliance with the Jin could be a basis for resisting the Mongols. Its drafter, Yi Kyubo, described the Jin emperor as universal ruler of the cosmos, whose virtue brought peace to the world. The Mongols, on the other hand, were "brutes and barbarians" (獷俗) so "insolent as to have forced the displacement of the imperial realm," an allusion to Jin court's exile to the south. Yi showed the sincerity of the Koryŏ king through tears that "flowed down in torrents" upon witnessing the "accumulated piles of [Jin] imperial letters." The emissary bearing the letter, however, never reached the Jin court. The Mongols had began their final assault on the Jin's last strongholds, destroying it a year later.95

Only four years later, Yi Kyubo found himself arguing for the sincerity of Koryŏ's allegiance to the very "brutes and barbarians" of the 1234 Jin letter. The eternal commitment to the Jin notwithstanding, Yi Kyubo transferred the same effusive adulations once reserved to the Jin to the Mongols in his 1238 diplomatic memorial to their ruler Ogodei Khan (r. 1229--1241). In this appeal, he deflected Mongol accusations of insincerity:

Your magnanimity that understands forthrightness has been laid bare to us....Humbly yours, this servant dwells afar in the barren marches and improperly occupies a humble fief. And so, this ignoble, small country would need to depend on a Great State. Still more, the Sage that we have been expecting has just descended. As one among the vassals who hold on to their lands, how dare we not submit with sincerity?96

The Mongols suspected Koryŏ of submitting only for necessity's sake, a way to avert an existential threat. Yi Kyubo transformed this existential necessity into a compulsion of duty, an ethical necessity. Koryŏ had no choice but to be sincere in submission. It submitted not out of fear, but because recognizing the inevitability of the Mongol's imperial destiny was its moral obligation:

....How could one say that "this was taken out of necessity when the situation became difficult?" Though we are sincere, we have been doubted, and on the contrary elicited chastisement from our Ruler and Father, and so [You] have repeatedly sent armies to punish these transgressions. 97

Although as "ruler and father," the emperor always reserved the right to "punish these transgressions," Koryŏ's sincerity meant the chastisement was unjust. Instead, the emperor should have used this opportunity to demonstrate his all-encompassing virtue. Yi thus exhorted imperial magnanimity with promises of eternal tribute:

We humbly hope that Your Majesty, the Emperor, whose deep benevolence extends his generosity afar, whose virtue values life, would only not exert the might of his armies. With our old customs preserved, though our tribute of seas and mountains (i.e. local produce) is meager, how could we miss a single year? This is not only something for today, but something [we will fulfill] eternally.98

The assertion of sincerity and the declaration of fealty were tokens of negotiation, a way to express Koryŏ terms of peace to demand the cessation of war. At the same time, it also appealed to a vision of moral empire; Koryŏ demands of the Mongols were not made explicitly, but couched within the rhetorical logic of the document. Its appeals rested on assumptions about the moral prerogatives of the emperor; in portraying his motivations and his magnanimity in this way, the Koryŏ memorial did not seek an accurate depiction of who the Mongol ruler was, but a clear image of who he should be. Performing sincerity, through literary embellishment and the promise of tribute, was a political strategy.99

Declarations of sincere loyalty worked within the warp and woof of a broader rhetorical structure, in which ideals of empire were erected from claims of sentimental authenticity. The memorial asserted sincerity, foundational as it was to this construction, often at times when it was most suspect. In 1259, the Koryŏ sent its crown prince to the Mongols to sue for peace. He surrendered to Khubilai Khan, who restored him to the Koryŏ throne as King Wŏnjong (元宗 r. 1260--1274) in 1260. His position as king remained tenuous.100 In 1265, Wŏnjong returned to the Mongol court for several months to show Koryŏ's allegiance. After an imperial feast to bid the Koryŏ entourage farewell at Wanshou Hill, the Koryŏ ruler had his official Kim Ku compose a memorial expressing his gratitude.101 The overwhelming imperial beneficence "moved the [king's] bowels and saturated [his] marrow" so deeply that his "undrying tears and rheum" have left his "lapels and sleeves on the verge of crumbling away."102 Hyperboles of sentiment portrayed the emotive intensity of the Koryŏ king's reaction as indicating artless spontaneity, lest the gesture of submission be dismissed as political calculation.

The infusion of emotional authenticity shifted the political into a mode of familial sentimentality. The emperor's "utmost benevolence" made coming to court no different than "returning to one's father and mother."103 The familial metaphor, together with the intensity of emotional reaction, worked together with the rest of the letter to demand a relationship of reciprocity: "Though it is [a ruler of] small country who comes in person to court, [his arrival] can still aid in glorying Sagely Brilliance"104 The glorification, achieved in this letter by casting the Koryŏ ruler's emotional outpouring as testimony to imperial virtue, transferred political agency from the emperor-as-sovereign to the tribute-bearing vassal, subtly transforming the relative importance of their positions. The memorial's description of the imperial banquet as a "feast of calling deer" (鹿鳴之讌), further reinforced this positional shift. In the poem from the Book of Songs it alludes to, the deer beckon their own kind to forage, an affective evocation (xing 興) for a wise lord sharing his bounty with loyal followers. He shares his "baskets of offerings" in hopes that they will "love [him]" and "show [him] the perfect path." The lord and his vassals enter reciprocal relationship, since enjoying its fruits require both parties to play their proper roles.105 The allusion suited a description of an imperial banquet, but in this classical expression of rulership, the Koryŏ king as a "guest" was not to offer absolute obedience. Instead, he owed the emperor first his love and, most importantly, guidance toward moral rule. The munificence of the emperor, once expressed in the infinity of his virtue, power, and glory was transformed into an instrument of reciprocity. This image of the "calling deer" rephrased the political implications of Koryŏ's acquiescence. Not simply an expression of fealty, it also claimed for Koryŏ a dignified and important place as authenticator of and participant in the project of empire. In the logic of the diplomatic memorial, it is the vassal who made the ruler.

Portraying acquiescence to imperial sovereignty in terms of reciprocal relations between lord and vassal was a persistent trope in Korean diplomatic writing. Its iteration in the mid-thirteenth century was significant because it implicitly challenged the ideological principles that guided the Mongol wars of conquest, at least before the the fragmentation of the Mongol empire during the reign of Khubilai Khan. The desperate and drawn out war between Koryŏ and the Mongols resulted partly from divergent expectations of the Koryŏ court and the Mongols. During the early phase of Mongol expansion, the Mongols, according to William Henthorn, "regarded everything and everyone in a conquered nation as absolute chattel, a concept which differs considerably from the Chinese oriented system with which Koryŏ was accustomed."106 The discourse Koryŏ adopted in its memorials accompanied the Mongols as they shifted from what Herbert Franke has called an "unsophisticated and unconditional claim to legitimacy as universal rulers" of the time of Chinggis Khan to one that was attenuated by concepts of Confucian rulership with Khubilai's accession and the establishment of the Yuan Dynasty.107

In letters such as these, complex politics were flattened and redrawn along familiar classical tropes, making them pliable for reinterpretation within a fiction of moral empire. This process, one in which Koryŏ was complicit, legitimized Mongol-Yuan rule by connecting it to the hallowed past, and painted over troubling memories of its violent rise and the embers of Koryŏ's ruined cities with a broad brush dipped in imperial yellow. But, in declaring the sincerity of its submission and praising imperial endeavors, the Koryŏ presented a Trojan Horse. Unadulterated praise concealed the real function of these classical references. They pointed to the distant past only to raise standards for the present. Whereas Koryŏ eagerly celebrated Mongol military successes against others, when imperial ambitions impinged upon its own interests these very same allusions and classical models could be redeployed as bulwarks against Mongol overreach. While an emperor could do no wrong, the words used to praise him became the shackles for restraining his actions.

"Eternal the Eastern Fief"

Korean diplomatic documents exhibit a remarkable generic and stylistic stability across a millennium. Even as the existential threat of imperial invasion had abated, the rhetorical techniques honed in those contexts persisted. Few institutional practices in human history can boast this level of endurance. Read together, these documents appear repetitive, recycling old classical allusions into tired tropes of empire. The Recorded Notes of the Pagoda Tree Hall alone contains over six hundred examples of such memorials from the Ming period. A cursory perusal would not be able to distinguish one memorial from another, especially since many of them were for routine, yearly presentations. Common refrains, formulaic phraseology, and stereotyped references only add to a repetitiveness reinforced by their own rhetoric of timelessness. In every memorial the Korean king declared his intentions to "forever guard [his] fief in the Eastern Sea" and "always bless [the emperor's] longevity, [as eternal as] Southern Mountain" and his "sincere" admiration of the emperor and his court, albeit in different recombinations of allusions and turns of phrase.108 Like the issue sincerity discussed already, timelessness too, expressed both in the trope of eternal fealty and reflected in the temporal stability of the genre, was a mask for volatility.

The facility with which the Koryŏ transferred allegiances from the Jin to the Mongols suggests that the rhetoric of empire contained in these documents was wholly detached from historical experience: a veneer of hollow words rather than a means of substantive negotiation. The emperors of the moribund Jin and the ascendant Mongols received the same treatment as all-encompassing, virtuous, and benevolent universal rulers. The rhetorical ornaments in these documents, as tropes common in panegyric writing, could be used for conventional political flattery, but the examples discussed so far show that even the most hackneyed classical allusion could carry resonating messages. In the case of the Jin and Mongol letters, it was precisely their will to timelessness---the apparently ahistorical vision of empire---that in fact imbued them with their rhetorical power. The Koryŏ articulated Mongol rulership within the ethos and modality of imperial rule that it had once granted the Liao and Jin emperors. They did this even before the Mongol leadership had aspired to those ideas or accepted the imperial tradition as their own. Koryŏ, by engaging with the Mongols on the same terms and in the same mode as it had done with past empires, attempted to revive an imperial tradition that had been extinguished with the Jin's destruction.109 In other words, the Koryŏ memorial did not simply legitimate Mongol claims to imperial authority. By acknowledging these claims even before the Mongols made them for themselves, it attempted to fashion the very terms on which imperial authority was based by preemptively situating Koryŏ within an established tradition of empire.

Related to this effort to impose the imperial tradition on Mongol rulers, these Koryŏ letters and diplomatic dispatches also fostered a sense of cultural recognition among the Confucian officials at the Yuan court. This recognition enabled a site of political intercourse that remained productive through the end of the Yuan period. For example, Kim Ku, with the dispatches he wrote from 1260 until his death in 1274, earned the praise of Wang E (王鶚 1190--1273), a former Jin optimus responsible for reviving imperial rituals at the Mongol court.110 Mutual cultural identification between former Jin officials in Mongol service and the Koryŏ provided a requisite discursive space for casting Koryŏ's preservation as integral to imperial restoration and cultural revival. In this space of negotiation, Confucian officials occupied the center, whereas their Mongol overlords often appeared as marginal interlopers, the "barbarian" other that was the implied target of their civilizing project.111

Kim Ku's memorial of 1260, written to congratulate Khubilai Khan on his accession, offers an example of how imperial legitimacy could be encoded. Its praise of the Mongol ruler abstracted him within that classical idiom:

After a thousand ages, a new beginning arrives like the rising sun. [All those who] call the four seas home [are] recipients of Heaven's protection; upon the commencement of [this new] rule, [they] celebrate in unison. With veneration we serve the Sagely and Glorious succession to the mandate. Divine wisdom in decisiveness, He cultivates the literary (文) and sets aside the whip [of war]; dances of shields and feathers [fill] the two stairs. Administering government and disbursing benevolence, He assembles the tribute ships of a myriad nations. The Exalted Mandate is restored and his august fortune augmented. Upon thinking that I, Your Servant, on account of my return to inherit this fiefdom, am unable to be among those to prostrate before you at Court and only gaze towards the [imperial] court, I [now] doubly show my sincerity [that can] move mountains.112

The memorial portrayed Khubilai's accession as a new beginning, a grand restoration of the "Exalted Mandate [of Heaven]." His sovereignty was boundless, celebrated by "a myriad nations," among whom was the Koryŏ. In this memorial, Kim Ku, like Yi Kyubo before him, deployed conventional tropes, but their effects relied on allusions that extended the text's resonances beyond exalting imperial majesty or assuring dutiful allegiance. They wove together a structure of relevance that drew both from its immediate historical context and the classical canon. The allusive power of its images deployed encoded not just any vision of imperial legitimacy, but a narrowly specific one. Praising the emperor for "[cultivating] the literary (文)," and laying down arms, the memorial obliquely recalled the recent warfare between Koryŏ and the Mongols. Thus implicitly repudiating military aggression, it championed the primacy of civil virtue over martial force in its evocation of the "dances of shields and feathers." This reference to the "Counsels of Great Yu," as it did in the Koryŏ-Song memorials discussed earlier, represented the power of civil virtue. When the Sage King Shun campaigned against the rebellious Miao, his counselor Yu remonstrated against the use of force and called for "entire sincerity" (至諴感神 矧茲有苗) to move them instead. Taking Yu's advice, the sage king "led back his army" and "broadly diffused civil virtue and danced with shields and feathers on the two staircases [in his palace courtyard]" to bring about their submission.113 The memorial inverted the relationship of agency implied in the locus classicus. The Koryŏ did not dispatch "tribute ships" to recognize Mongol military prowess, but rather as the Miao did in days of yore, to pay obeisance to a ruler who commenced a new age of peace with his benevolent rule. The Koryŏ only submitted because the Mongols had set aside the "whip" of war. These rhetorical flourishes, not mere ornaments of political flattery, in fact encode normative political standards, shaping and defining what virtuous rulership entailed. In the process, Koryŏ authenticated not only Khubilai's virtue, but also the classical logic of empire itself. In it, civil virtue worked and was a viable alternative to martial force.

Koryŏ's submission thus became a symbol of sanction to the new imperial order. Subservience, then, was not declared without implicit conditions. Accompanying the 1260 memorial was a separate missive, which ostensibly thanked the Mongol emperor for releasing King Wŏnjong (元宗 r. 1260--1274) from captivity:

...having permitted me to return over a thousand leagues, You have comforted me in many ways, many times more than usual. As such, I have returned without injury, and gratitude overwhelms my heart. As soon as I arrive in my humble fief, you bestowe upon me enlightened instructions to honor me.114

Although the statements above credited Koryŏ's autonomy to imperial magnanimity, the Koryŏ king's own prerogatives were reasserted in the next line. The letter enumerated the "enlightened instructions" that had been promulgated:

[Your] edict said, "Your old territory will be restored and you will eternally be [our] eastern vassal." Receiving the extended beneficence from this Sagely Dawn, I will now continue to guard the lands of my forebears.115

Through selective quotation of Khubilai's edict, the Koryŏ letter reiterated the emperor's assurances to Wŏnjong, recast as guarantees of Koryŏ's perpetual survival. This reminder implored the emperor and his servants to stay true to their word. Given the tenuousness of Mongol-Koryŏ relations, poisoned by decades of warfare, neither Khubilai's promises of Koryŏ's preservation nor Koryŏ's own declarations of loyalty were taken for granted. When this atmosphere of mistrust hung overhead, statements guaranteeing Koryŏ "eternal" status as a "vassal" amounted to little. The Koryŏ letter thus quoted Khubilai's original edict:

'If you set straight your territory and boundaries and settle the hearts of your people, then my armies will not come ever again. Now that I have made such a declaration, I will certainly not eat my words.' A great declaration thus made; the utmost benevolence can be seen. With the arrival of one letter wrapped in silk, a whole nation's tears fall down at once.116

Khubilai's support of the Koryŏ throne and his promise not to attack Koryŏ again became a mark of great virtue, an act of benevolence that could move even "trees and stones." The Koryŏ king then promised that "his descendants will die to repay" this honor, swearing "upon the mountains and seas" that he "will never change, and eternally observe his duty towards the land of his charge."117 In this manner, the Koryŏ letter transmuted Khubilai's policies into a gesture of utmost benevolence, and along with it, the Koryŏ ruler acquired for himself and his descendants an eternal mandate. The preservation of the kingdom of Koryŏ was no longer a reprieve from inevitable destruction or a precarious survival scrounged from the emperor's pleasure, but a matter of duty: Koryŏ's duty to the emperor. The perpetuity of Koryŏ rule became the mechanism for repaying the emperor. Koryŏ, once a territory to be conquered, had integrated its preservation into the logic of imperial rule.

Asserting such promises in one memorial did not guarantee the interests of the Koryŏ monarchy. Conquering regimes tend to forget their promises, especially to those who cannot resist them, and the terms of this relationship had to be repeatedly reasserted. The wording of Khubilai's edicts, as it is interpreted in this memorial, came to be deployed repeatedly throughout the late Koryŏ to defend the kingdom's territorial integrity, the well-being of its monarchs, and the sanctity of its customs. Part of affirming this relationship was reiterating Koryŏ's commitment to Khubilai's imperial project.118 For the Koryŏ, and later the Chosŏn, repeated assertions of consistent tropes was not simply reiterations of preexisting constants, but the transformation of political arrangements forged in one historical moment into normative constants to be leveraged in the future.119

Diplomatic memorials constructed eternity in content, form and practice. The genre's stable persistence through time echoed with a rhetoric of timelessness reaching both backward to the sage kings of yore and forwards to an infinite future. These documents project a vision of empire that transcended the political exigencies of the moment and the finite scale of mortal time. This timelessness helped construct both imperial legitimacy and the legitimacy of Korea's relationship with empire. Timelessness, then, equated imperial authority with cosmic ontology, and thus naturalized its political power.

On the other hand, diplomatic documents were invariably framed within the scale of dynastic time. For Koreans, how imperial time was inscribed had symbolic significance for the recognition of imperial legitimacy, as JaHyun Kim Haboush has shown. For the imperial audience of Korean documents, evidence of "observing the proper lunation" (尊正朔), i.e. following the imperial calendar, was an important symbol of Korean sincerity. Mongol-Yuan officials wanted to make sure the Koryŏ did not observe Song lunations upon its surrender. A Ming loyalist was moved to tears when he read Korean books that marked time with the Ming calendar. A Qing emperor was miffed when he discovered that Koreans still observer Ming reign eras. For all of them, the observation of specific dynastic time demonstrated political fealty.120

Loyalty belonged to dynastic time, but the memorial genre itself transcended it. These two temporal scales were in tension. Korea's relationship with empire was couched in a rhetoric of eternity that implied its values and political arrangements existed beyond dynastic time. Yet, empire itself was temporally inscribed and circumscribed, a momentary manifestation of an immanent moral order. Was the relationship conceived in these memorials one that existed beyond the confines of dynastic history? Or, was it one firmly located within the institutional structures of one particular dynastic state? In other words, did the Korean memorial declare its loyalty to a particular emperor, a particular state, and a particular ruling family, or as an affirmation of the imperial system and its tradition as a whole?

If one, as many scholars have done, understands Korean relations with "China" in terms of a transdynastic ordering of East Asian states with the "Chinese" empire at the center of a spatial imagination and its ruler the apex of a hierarchy of monarchs (i.e. the tributary system), then the answer should be the latter. The Korean memorial, then, by configuring dynastic time in a cosmic scale, effectively elevated spatial and temporal rulership into something transcendent and universal. These memorials were thus producing a sense of an eternal, transdynastic order within dynastic time.

Following this line of reasoning in historical analysis, however, risks mistaking the rhetorical construction of eternity in such texts for unadulterated reality. The "tributary system" appears as a consistent structural feature only because those who made use of its practices willed it to be so. The strategy in this chapter, and throughout this dissertation then, is to posit an alternative ways of thinking about these memorials and other diplomatic genres. Although these practices took on an apparent fixity of form, they were in fact sites for contestation and negotiation. Genres of imperial legitimation on the surface, the Korean diplomat and memorial writer participated in the production of empire to shape and ultimately define imperial authority. The memorial was not a reflection of the "tributary system," but a central process through which such structures were recreated and reproduced. The sense of stability then is an illusion sustained by numerous discrete acts of contestation and rewriting. Each individual memorial might appear infinitesimal in the grand scheme of things, but their accumulated effect over the longue durée was the illusion of a timelessness transcending dynastic time. It infused the terms of Korea's relationship with empire a sense of immobile permanence. While this image meant Korean rulers could not assert sovereign authority completely independently from empire, it also fixed Korea's ontological status as an inviolable eternal entity, impervious to the vicissitudes of political fortune.

Conclusion

Diplomatic memorials gradually settled into a documentary form with stable generic conventions. Sŏ Kŏjŏng's Literary Selections provided ready models for future composers. A cursory examination of these letters in the Ming and Qing period exhibit a remarkable stylistic and rhetorical consistency. When the Chosŏn court official Sin Yong'gae (申用漑 1463--1519) compiled a continuation of Sŏ's anthology, he did not include any new diplomatic memorials. In contrast to Sŏ and his collaborators who devoted nearly a dozen fascicles to the genre, Sin's compilation included only two mock memorials, written by Chosŏn literati in the voice of imperial officials.121 The exclusion of diplomatic memorials did not indicate a decline in the importance of relations with the imperium. Sin Yong'gae active in diplomacy with the Ming, the reign of King Chungjong during which he made his career, was one of the most active periods of Chosŏn-Ming diplomacy. One can surmise that for Sin, Sŏ's anthology was already an adequate guide for compositions in this genre.

After the Manchus conquered the Ming, the Korean practice of sending such memorials continued. The weight of rhetoric continued to demand much of a memorial drafter's talent. Writing mock memorials became a major subject of Korean civil service exams through the end of the Chosŏn period.122 In 1705, the Manchu Qing sought to fix the Korean memorial by promulgating specific templates formalizing not only the style of the document, but also its rhetorical structure. The Qing complained that "all the memorials from the myriad [emphasis mine] states followed a fixed form, but only the memorials from Korea differed." Despite this rhetoric of universality, the Qing court only received similar memorials from the Vietnamese and Ryukyuans, and the formats demanded of the Koreans never applied to them.123 The Qing thus disguised a targeted attempt at regulating Korean memorials in terms of a general reform of memorial style. Aware of Korean misgivings about Manchu legitimacy, the Qing was concerned that the Chosŏn might slip in references to its "barbaric" origins. A Chosŏn memorial included the controversial character i/yi 夷. There were a wide-range of possible meanings. Although the memorial used the character in the sense of "awakening," the Qing evidently saw its use to be an insinuation of "barbarity," one of the character's other possible senses.124 By enforcing a strict form for memorials, and occasionally protesting to the Chosŏn the misuse of certain words and faulty prosody, it could enforce its political authority through the regulation of literary standards.125